Almost 40 years ago, in 1981, women cheered during a rally for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment. Today, Virginia, just across the Potomac River, could become the crucial 38th state to approve the constitutional change. Bettmann / Getty Images

Former Associate Editor, Special Projects

Election Day in 2019 didn’t involve any high-profile House or Senate or Presidential seats up for the taking, but it had historic consequences nonetheless. In the Commonwealth of Virginia, voters handed Democrats control of both its statehouse chambers, and within a week of the 2020 legislative session, the new majority voted to make Virginia the 38th state to ratify the Equal Rights Amendment (E.R.A.). Nearly a century after it was first suggested, the E.R.A. now stands a renewed chance of making it into the Constitution as the 28th Amendment.

What are the origins of the E.R.A.?

In 1921, the right for women to vote freshly obtained, suffragist Alice Paul asked her fellow women’s rights activists whether they wanted to rest on their laurels. The decision at hand, she said, was whether the National Woman’s Party would “furl its banner forever, or whether it shall fling it forth on a new battle front.”

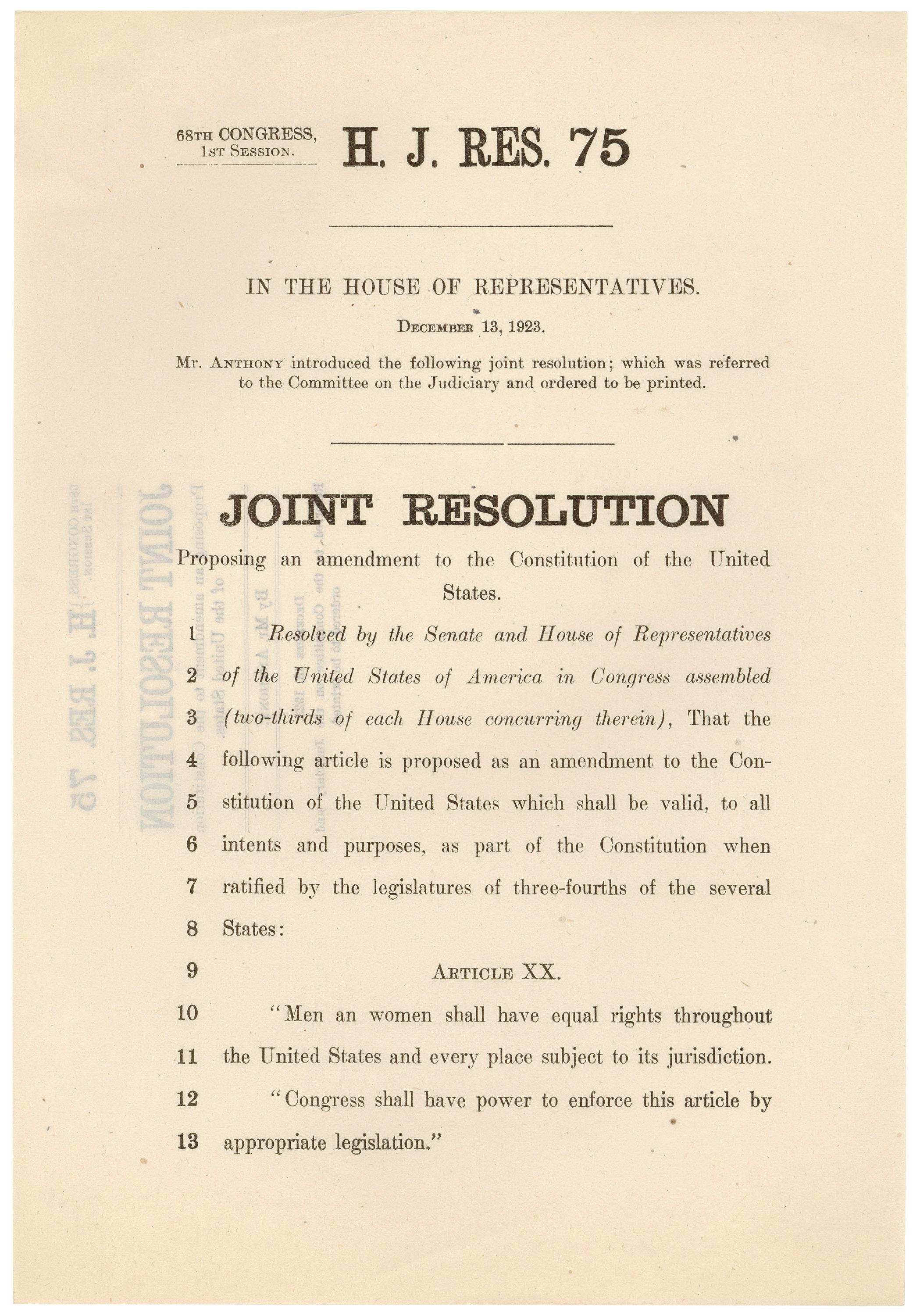

Eventually, Paul and some fellow suffragists chose a new battle: a federal guarantee that the law would treat people equally regardless of their sex. Paul and pacifist lawyer Crystal Eastman, now considered the “founding mother of the ACLU,” drafted the “Lucretia Mott Amendment,” named after the 19th-century women’s rights activist. The original E.R.A. promised, “Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

Paul’s insistence on a constitutional amendment proved to be controversial even in suffragist circles. Paul and other, like-minded activists believed an amendment would be the fastest path to social and economic parity for women, especially because their efforts to implement similar legislation on a state level hadn’t proved successful. But other prominent advocates objected, worried that the E.R.A. went too far and would eliminate hard-won labor protections for women workers. Florence Kelley, a suffragist and labor reformer, accused the N.W.P. of issuing “threats of a sex war.” And, as historian Allison Lange points out in the Washington Post, the N.W.P.’s new direction left behind women of color, who couldn’t exercise their newfound voting rights due to racially biased voter suppression laws.

Nevertheless, the N.W.P. persuaded Susan B. Anthony’s nephew, Republican Representative Daniel Anthony, Jr. of Kansas, and future vice president to Herbert Hoover Charles Curtis to introduce the earliest version of the E.R.A. to Congress in 1923. Despite repeated reintroduction, the E.R.A. got nowhere in the face of continued opposition from the labor and Progressive movements. The Republican Party added the E.R.A. to its platform in 1940, followed by the Democratic Party four years later. In 1943, as part of an effort to make the amendment more palatable to legislators, Paul rewrote the text to echo the “shall not be denied or abridged” wording of the 15th and 19th Amendments. Even rewritten, writes Harvard political scientist Jane Mansbridge in Why We Lost the ERA, the proposition made no headway until 1950, when it passed the Senate, saddled with a poison pill provision from Arizona Democrat Carl Hayden that E.R.A. advocates knew would nullify its impact.

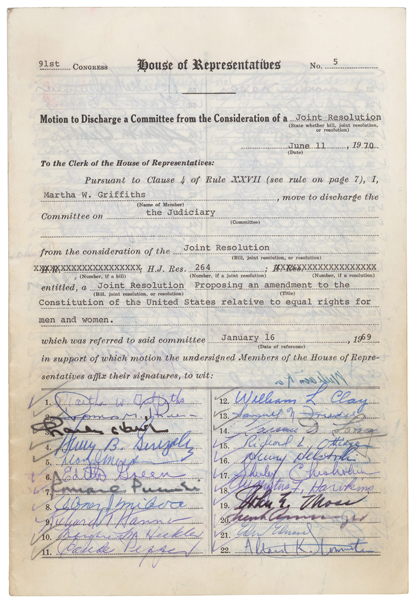

Finally, amid the social upheaval, civil rights legislation and second-wave feminism of the 1960 and ’70s, the E.R.A. gained traction. In 1970, Democratic Rep. Martha Griffiths of Michigan brought the E.R.A. to the floor of the house by gathering signatures from her colleagues, bypassing a crucial pro-labor committee chair who’d blocked hearings for 20 years and earning her the nickname the “Mother of the E.R.A.” The amendment won bipartisan support in both chambers; the House approved it in October 1971 and the Senate in March 1972. With Congress signed on, the next stage of the process to change the Constitution began: ratification by the states.

How does ratification work?

The Founding Fathers knew the Constitution wouldn’t age perfectly; in the Federalist Papers, James Madison forecasted, “Useful alterations will be suggested by experience.” The amendment process they devised was meant to provide a Goldilocks-like middle ground between “extreme facility, which would render the Constitution too mutable; and that extreme difficulty, which might perpetuate its discovered faults.” Article V of the Constitution lays out their solution: Amendments can be offered up for consideration by a two-thirds majority in the House and the Senate (or, although it’s never happened, a convention of two-thirds of the states). After passing that threshold, the would-be change has to be approved by three-fourths of the states to actually become part of the Constitution. States certify an amendment by passing it through their legislatures or a state convention, although that method has only been deployed once, for the amendment that repealed Prohibition. In Virginia, for instance, that means the Commonwealth’s Senate and House of Delegates must vote for it; unlike most legislation, amendment ratification does not require the governor’s signature.

Why didn’t the E.R.A. get ratified after Congress passed it?

In the first nine months after the E.R.A. was passed to the states, it racked up 22 ratifications in states from Hawaii to Kansas. That number swelled to 33 states by the end of 1974, and Gallup polls showed that almost three-fourths of Americans supported the E.R.A. But, says Mary Frances Berry, a University of Pennsylvania historian who wrote a book cataloguing the E.R.A.’s failure to launch, “The folks that were pushing it failed to notice that you needed states, not just popular opinion.”

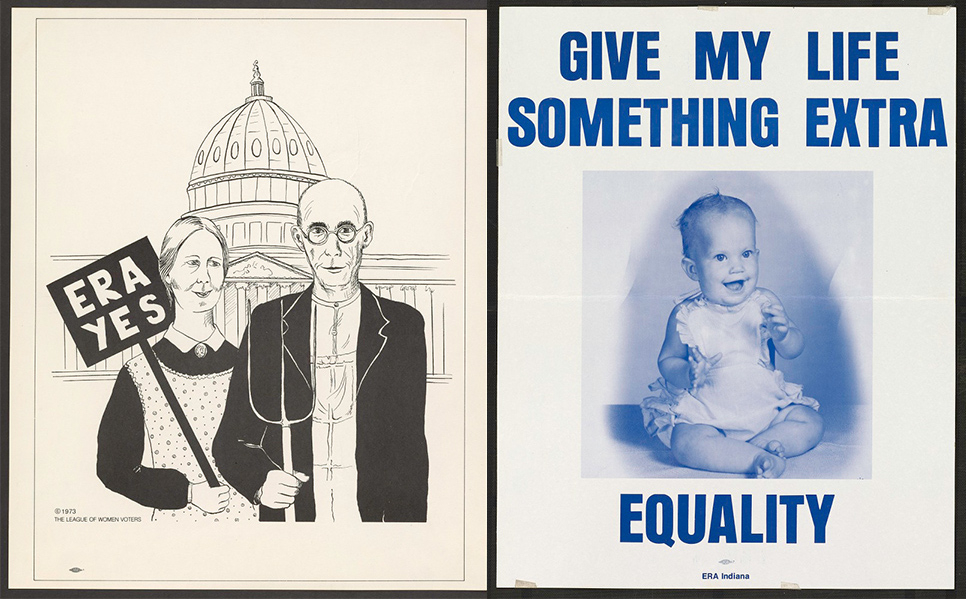

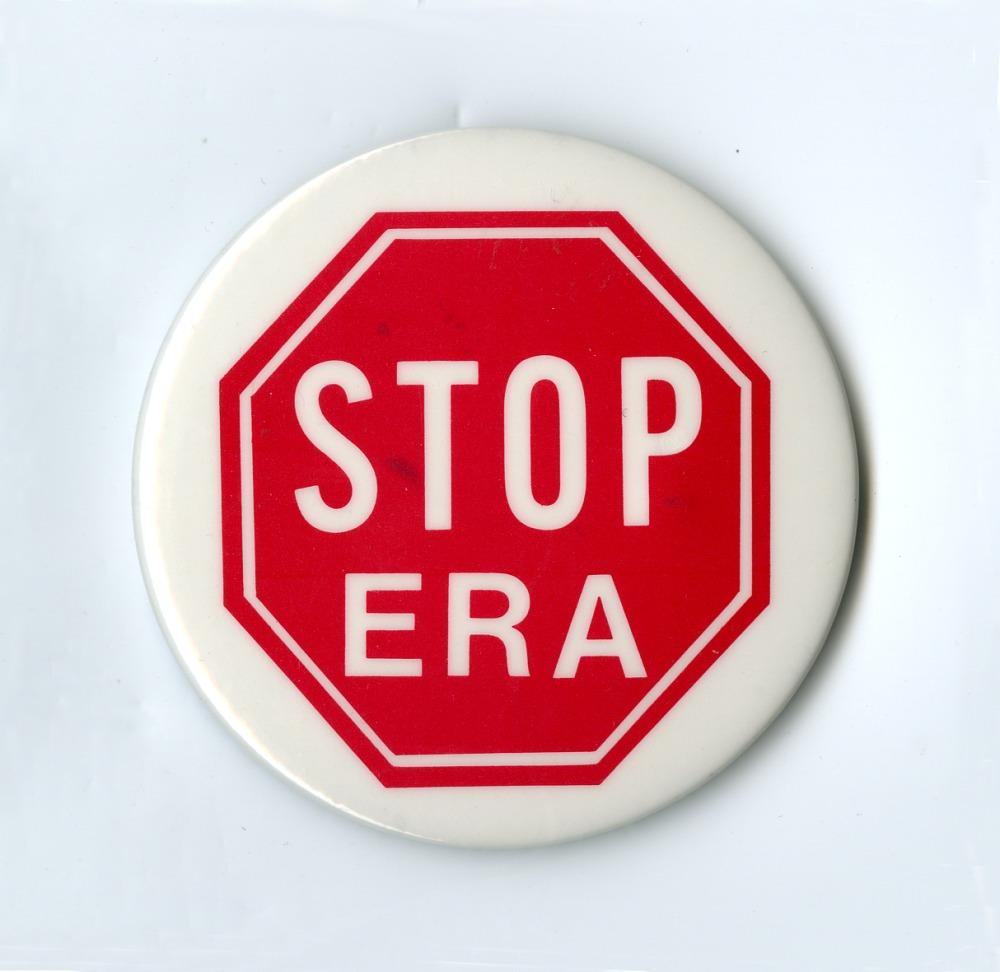

The E.R.A. had the support of the majority of the public during the years it was up for ratification, according to Gallup polling. But that enthusiasm waned over time, and its political momentum stalled, thanks to the anti-E.R.A. organizing efforts of conservative, religious women like Illinois’ Phyllis Schlafly.

Schlafly’s organizations, STOP (an acronym for “Stop Taking Our Privileges”) ERA and the still-active conservative interest group Eagle Forum, warned that the E.R.A. was too broad, that it would eliminate any government distinctions between men and women. They circulated printouts of Senate Judiciary Chair Sam Ervin’s—popular for his handling of the Watergate investigation—invectives against it and trotted out socially conservative specters such as mandatory military service for women, unisex bathrooms, unrestricted abortions, women becoming Roman Catholic priests and same-sex marriage. STOP ERA members would lobby state governments, handing out homemade bread with the cutesy slogan, “Preserve Us From a Congressional Jam; Vote Against the E.R.A. Sham.”

Feminism, Schlafly told the New York Times, was “an antifamily movement that is trying to make perversion acceptable as an alternate life-style,” and the E.R.A., she portended, would mean “coed everything—whether you like it or not.” Schlafly’s status-quo message stuck and swayed politicians in states that hadn’t yet ratified the E.R.A. like Florida, Illinois, Georgia and Virginia.

This anti-E.R.A. sentiment grew against the backdrop of a ticking clock: in keeping with custom, lawmakers gave the E.R.A. a seven-year deadline to obtain ratification. In the early 70s, the arbitrary time limit—a tradition that began with political maneuvering around the 18th amendment (Prohibition)—had unsettled some. “There is a group of women who are so nervous about this amendment that they feel there should be unlimited time,” said Griffiths, the E.R.A.’s sponsor in the House. “Personally, I have no fears but that this amendment will be ratified in my judgment as quickly as was the 18-year-old vote [the recently passed 26th Amendment]. I think it is perfectly proper to have the 7-year statute so that it should not be hanging over our heads forever. But I may say I think it will be ratified almost immediately.”

Many of Griffiths’ peers shared her optimism. “I don’t think that they projected that [ratification] would be a problem,” says University of Pennsylvania historian Berry. “I don’t think they realized how hard it was going to be.”

As 1979 approached and the E.R.A. remained three states short, the Democrat-controlled Congress extended that deadline to 1982, but to no avail—not a single additional state signed on to the amendment. At Schlafly’s victory party on July 1, thrown the day after the clock ran out for her legislative nemesis, the band played “Ding Dong, the Witch Is Dead.”

Hasn’t the window for ratification passed?

Yes, the 1982 deadline is long gone, but legal scholars have argued that that’s reversible. The William & Mary Journal of Women and the Law makes the case that Congress can re-open the ratification window, pointing out that not all amendments (like the 19th) include a time limit and that Congress extended the deadline once before. While the Supreme Court previously ruled that amendments must be ratified within a “sufficiently contemporaneous” time, it also batted the responsibility of defining that window to Congress, as a 2018 Congressional Research Service report outlines. The most recent amendment, the 27th, was adopted in 1992 with the Department of Justice’s seal of approval—it was written by James Madison in 1789 as part of the Bill of Rights and had spent 203 years in limbo. (The 27th Amendment prohibits members of Congress from giving themselves a pay raise right before an election.)

While this precedent seems favorable, it’s worth noting that five states—Nebraska, Tennessee, Idaho, Kentucky and South Dakota—rescinded their early ratification of the E.R.A. as socially conservative anti-E.R.A. arguments gained ground. Legal scholars debate the validity of that rescission, as there is historic precedent implying that ratification is binding: Ohio and New Jersey tried to take back their approval of the 14th Amendment in 1868, but despite this retraction, the official documents still include them on his list of ratifying states. Robinson Woodward-Burns, a political scientist at Howard University, points out for the Washington Post that a similar situation cropped up with the 15th and 19th Amendments, “suggesting that states cannot withdraw ratification.” In 1939, the Supreme Court declared that ratification reversal “should be regarded as a political question” and therefore, out of its purview.

Until January 2020, the E.R.A. remained in the company of other passed-but-never-fully-ratified “zombie amendments,” to curb a phrase from NPR’s Ron Elving. Among them are amendments granting the District of Columbia voting representation in Congress (passed by Congress in 1978 and ratified by 16 states before it expired), an 1810 amendment prohibiting American citizens from receiving titles of nobility from a foreign government (sorry Duchess Meghan!) and the the Child Labor Amendment (passed by Congress in 1937 and ratified by 28 states). The Corwin Amendment, a compromise measure passed in the leadup to the Civil War and supported by Abraham Lincoln, is a more sinister, still-technically-lingering amendment. It would have permanently barred the federal government from abolishing slavery.

What happened in the years since the 1982 deadline passed?

The E.R.A. didn’t altogether fade from policymakers’ consciousness after its defeat. From the ‘90s until now, congresswomen and men routinely introduced bills to disregard the ratification window or resubmit the amendment (or an updated version that would add the word “woman” to the Constitution) to the states. No state had approved the E.R.A. in 40 years when, in 2017, Nevada’s newly Democratic legislature ratified the E.R.A. The next year, Schlafly’s home state of Illinois followed suit. On January 15, 2020, the Virginia General Assembly approved the E.R.A., setting up a heated constitutional debate.

Virginia has come tantalizingly close to ratification before. In 1982, the Commonwealth’s last chance to vote for the E.R.A. before the deadline, a state senator hopped on a plane out of town, conveniently missing the roll call and evading the 20-20 tie that would have secured a pro-E.R.A. tiebreak vote from the lieutenant governor. Earlier in 2019, the E.R.A. passed the Virginia Senate but was stymied in a House subcommittee.

What would come next? “We fully anticipate that there will be a Supreme Court decision involved,” Krista Niles, the outreach and civic engagement director at the Alice Paul Institute, told the New York Times. But the Supreme Court’s scope of authority over amendments is nebulous based on precedent, writes Robert Black for the National Constitution Center.

What would the adoption of the E.R.A. mean today?

Women’s rights have come a long way since Alice Paul first proposed the E.R.A. States have enacted their own laws broadly prohibiting sex-based discrimination, and thanks to a feminist legal campaign led by Ruth Bader Ginsburg and the ACLU, the Supreme Court recognized sex discrimination as violating the equal protection clauses of the 5th and 14th Amendments in cases liked Frontiero v. Richardson and United States v. Virginia. Due to this progress, the E.R.A.’s ramifications wouldn’t feel quite as revolutionary today, says Berry, but “it would still have some impact, because it is much better to have a basis for one’s rights in the Constitution.”

Current sex-discrimination law rests on judicial interpretations of equal protection, which can vary by ideology. If ratified, the E.R.A. would give policymakers a two-year buffer period to bring existing laws into compliance, and after that, policies that differentiated by sex would be “permitted only when they are absolutely necessary and there really is no sex-neutral alternative,” explains Martha Davis, a law professor at Northeastern School of Law. It would likely still be permissible, she says, to shape laws differently to address physical characteristics that are linked to sex assigned at birth, like breastfeeding or pregnancy, and privacy qualms like separate-sex bathrooms.

Other laws, like the mandated draft for only men or immigration policy that differs based on a parent’s gender, might change, and conservative opponents have argued that it could impact welfare programs aimed at women and children.

Now, one century after the 19th Amendment took effect, Virginia has approved the legislation Alice Paul saw as suffrage's successor, and the 97-year-old amendment's future is up to Congress and the courts.

Editor's Note, January 15, 2020: This story has been updated to include Virginia's 2020 vote to ratify the E.R.A.

Get the latest History stories in your inbox?

Lila Thulin is the former associate web editor, special projects, for Smithsonian magazine and covers a range of subjects from women's history to medicine.