The of 1765 was the first direct tax imposed on the 13 American colonies by the Parliament of Great Britain. It required the colonists to pay a tax on all printed materials including newspapers, legal documents, magazines, and playing cards. This triggered a wave of resistance across the colonies and helped spark the American Revolution (c. 1765-1789).

At the end of the French and Indian War (1754-1763), as the North American theater of the Seven Years War is often called, the belligerent powers signed the Treaty of Paris of 1763. While most of the colonial territories captured during the war were returned to their previous owners, there were several notable exceptions: the vanquished Kingdom of France, for instance, was forced to cede Canada and all its North American holdings east of the Mississippi River to its victorious rival, Great Britain. This greatly expanded Britain’s colonial territory in North America but also came with a new set of problems, particularly regarding defense. The ink on the peace treaty was barely dry when a steady stream of American colonial settlers began trickling into the newly won lands between the Appalachian Mountains and Mississippi River. It did not take long for these settlers to begin fighting with the displaced Native American nations who lived there.

AdvertisementA Royal Proclamation issued in October 1763 that forbade American colonists from settling this region went largely ignored; conflict between white settlers and native peoples escalated into the bloody Pontiac’s Rebellion (1763-1764). Though the native revolt was crushed by the end of 1764, the destructiveness of the conflict convinced Parliament that new steps would have to be taken for the defense of the American colonies. It was decided, therefore, that a standing army of 10,000 British regulars would be dispatched to keep the peace in North America. The maintenance of such an army was estimated to cost an annual £200,000, an expense that Parliament could ill-afford, as it was grappling with mountains of postwar debt. A new source of revenue would have to be found and, since the money was going toward the defense of the American colonies, many in Parliament believed it only fair that the colonists themselves footed part of the bill.

A tax on paper documents would affect more colonists than the previous molasses duties.

On 5 April 1764, British Prime Minister George Grenville (l. 1712-1770) passed an act through Parliament that would become known as the Sugar Act. An extension of the existing Molasses Act of 1733, Grenville’s Sugar Act imposed a tax of 3 pence per gallon on molasses produced outside of the British Empire, as well as restricted the trade of other valuable colonial goods, such as lumber, to Britain alone. The Sugar Act proved unpopular amongst colonial merchants, who relied on foreign molasses from the Dutch and French West Indies for the broader triangular trade; merchants primarily in the New England colonies protested the act, boycotting luxuries from Britain and petitioning Parliament to repeal it. Occasional instances of violence broke out, particularly in Rhode Island, as British customs officers were bullied, intimidated, and in some cases jailed by colonial officials.

Although the Sugar Act outraged the colonial merchant class, the level of overall protest remained low, as the tax did not affect the every-day American. But by mid-1764, rumors began circulating that Grenville meant to implement another tax on paper documents, which would affect more colonists than the previous molasses duties. Colonial anxieties continued to rise over what Grenville’s new tax would entail and, on 2 February 1765, four agents representing the colonies met with Grenville in London to find out. The agents, who included the already famous Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790) of Philadelphia, told Grenville that the colonies were worried about the forthcoming Parliamentary tax, and that the colonial assemblies preferred to tax themselves. If the colonies lost this ability, the fear was that Parliament would inadvertently subvert the institutions of representative government in America, since royal governors would no longer have a reason to convene the colonial assemblies. Grenville recognized the colonists’ concerns but expressed his belief that the Americans had to help pay for their own defense; since the agents had not presented a viable alternative plan, Grenville decided to go ahead with the vote.

On 6 February 1765, Grenville brought his resolution before the House of Commons. Unlike the Sugar Act, which Parliament had passed without opposition, there was lively debate surrounding the proposed Stamp Act. Describing the Americans as “children planted by our care,” and “nourished up by our indulgence,” Charles Townshend asked his fellow MPs why the colonists should be allowed to refuse to shoulder the financial burden of their own defense. To this, the Anglo-Irish Colonel Isaac Barre issued a dynamic reply:

AdvertisementThey planted by your care? No! Your oppression planted them in America. They fled from your tyranny to a then uncultivated and unhospitable country – where they exposed themselves to almost all hardships to which human nature is liable…They nourished up by your indulgence? They grew by your neglect of them: as soon as you began to care about them, that care was exercised in sending persons to rule over them…to spy out their liberty, to misrepresent their actions and to prey upon them; men whose behavior on many occasions has caused the blood of these Sons of Liberty to recoil within them (Middlekauff, 79).

The oratory of Colonel Barre and his compatriots was impressive but was not enough to stop the stamp bill from receiving its first reading on 13 February. The opposition asked to introduce several petitions from the colonies of Massachusetts, Virginia, and Connecticut, but the House of Commons refused to hear them. The bill was approved in the House of Commons by a vote of 245-49 and was passed unanimously in the House of Lords. On 22 March, George III of Great Britain (r. 1760-1820) affixed his royal signature to the bill, and the Stamp Act became law. It was set to go into effect on 1 November 1765.

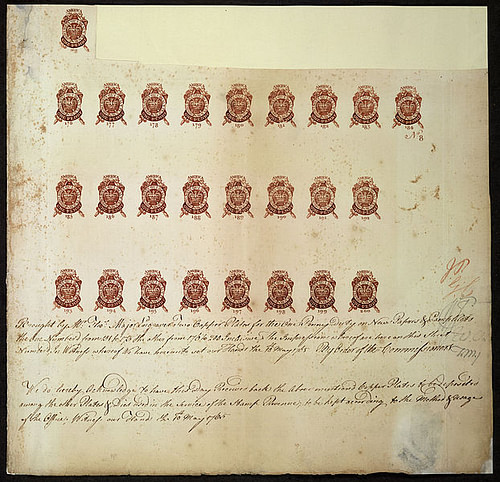

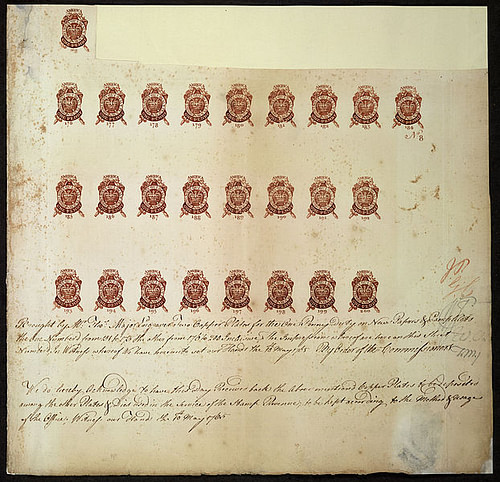

While the unpopular Sugar Act had been a tax on trade, the Stamp Act was the first direct tax imposed by the Parliament of Great Britain on the American colonies. It required that all paper documents – including wills, marriage licenses, legal contracts, diplomas, newspapers, calendars, almanacs, and playing cards – carry stamps, which were representative of the tax. The stamps would be distributed by political appointees, and could only be purchased with British hard currency, as opposed to the American paper currency that was more plentiful in the colonies. Anyone caught violating the act was to be subjected to a vice admiralty court; in other words, they would not be tried by a jury of their peers but by a judge appointed by the Crown.

The idea of ‘no taxation without representation’ became one of the building blocks of the American Revolution.

To understand why the Stamp Act was so outrageous, one must first understand the differing viewpoints that the colonists and Parliament held regarding the American identity. Certainly, in 1765, both the colonists themselves and Parliament would have agreed that the colonists were Britons; after all, the colonists were subjects of King George III and part of the broader British Empire. However, the colonists believed that as Britons, they had retained the rights of Englishmen even in the New World, including the right to tax themselves; this idea of representation was one of the basic pillars from which Parliament derived its authority. For this purpose, the American colonists had raised their own colonial legislatures. Parliament, however, saw things differently; while the Americans enjoyed the rights of Britons, they were no different than the 90% who owned no land and could therefore not vote in Britain. Parliament claimed to virtually represent the interests of the colonists who should, after all, be subject to the same mandates that affected the rest of the king’s far-flung subjects.

AdvertisementSo, the Stamp Act, and the Sugar Act before it, were protested based around the belief that Parliament had no authority to tax the colonies because the colonists had no representatives in Parliament. This idea of ‘no taxation without representation’ became one of the building blocks of the American Revolution. It was championed early on by prominent colonists like Samuel Adams (1722-1803) of Boston, who warned that the imposition of a Parliamentary tax without the colonists’ consent would transform the Americans from “the character of free subjects to the miserable state of tributary slaves” (Schill, 73).

The colonies received the news that the Stamp Act had passed in early April, and for six weeks no colonial legislature appeared eager to take the lead in challenging it. For the Virginia House of Burgesses, it appeared that the tax would not be discussed and, as the legislative session wound down at the end of May, most of the legislators set out for home. Only 39 of the 116 legislators remained when the 29-year-old Patrick Henry (1736-1799), attending his first session, stood and proposed a series of resolutions. Known as the Virginia Resolves, the first four stated, in part:

In summation, the resolves acknowledged that the colonists retained the same rights that Englishmen enjoyed, including the right to tax themselves. The eloquent Henry succeeded in getting the Resolves passed by the rump of the House of Burgesses, and their text was reprinted in newspapers across the colonies. By the end of 1765, the lower houses of eight other colonies followed Virginia’s example by renouncing the Stamp Act and rejecting Parliament’s authority to tax them altogether.

AdvertisementFrom 7-25 October 1765, representatives from nine of the Thirteen Colonies met in New York City to discuss a unified response to the Stamp Act; afterward known as the Stamp Act Congress, this was the first major gathering of colonial representatives since the 1754 Albany Congress. During this meeting, the representatives issued a Declaration of Rights and Grievances, in which they echoed many of the claims made in the Virgnia Resolves: that they retained the rights of Englishmen and rejected any Parliamentary taxes on the basis that the colonies were unrepresented in Parliament. Delegates conceded that Parliament had the right to legislate for the colonies in matters of ‘external policy’, which was loosely defined as issues of common interest to the British Empire as a whole. The Stamp Act Congress unnerved Parliament, who had not expected the colonies to coordinate in such a way; the Congress is often recognized as the first unified political action made by the colonies during the American Revolutionary era.

As Virginia’s House of Burgesses and the Stamp Act Congress pushed back against the tax with petitions and rhetoric, other colonists were eager to take direct action. The epicenter of the Stamp Act riots was in Boston, Massachusetts, where a small group of men had formed themselves into a group known as the Loyal Nine. This group included artisans, shopkeepers, and even the printer of the Boston Gazette; though Sam Adams and John Hancock (1737-1793) were not members, they were closely involved with the group. Hoping to recruit some ruffians to do their dirty work, the Loyal Nine turned to the North and South End mobs of Boston, rival gangs which were known for their annual brawls on Guy Fawkes’ Day. Sometime in early 1765, the two mobs put aside their differences and joined into a unified group under the leadership of Ebenezar MacIntosh, a cobbler.

The Loyal Nine approached MacIntosh and redirected the fury of the mobs toward the Stamp Act and its collectors. In particular, the Loyal Nine targeted Andrew Oliver, the distributor of stamps for Massachusetts. On 14 August 1765, an effigy of Oliver was discovered hanging from an Elm tree. Lt. Governor Thomas Hutchinson of Massachusetts ordered the sheriff to cut the effigy down, but he refused; the sheriff argued that the crowd was in such a frenzy that any attempt to do so would cost him and his men their lives. At dusk, MacIntosh roused the combined North and South End mobs, took the effigy from the tree, and marched toward Oliver’s office, which was promptly torn to the ground. The mob then ransacked Oliver’s house. Calls went up to find and kill Oliver, and several houses were searched; the fact that Oliver had fled to Castle William in the Boston Harbor probably saved his life.

Shaken by this near-death experience, Oliver resigned the next day. Unsatisfied, the mob attacked the home of Lt. Governor Hutchinson, seen as a supporter of the Stamp Act, on 26 August; everything movable was stolen from the house, and Hutchinson himself probably only survived because he was not home. These riots became celebrated throughout the colonies; the tree on which the effigy of Oliver was hanged became the first ‘Liberty Tree’, and a new group of colonial patriots, called the Sons of Liberty, dated the founding of their organization to these August riots.

Similar riots occurred in other colonies. On 27 August in Newport, Rhode Island, protestors hung effigies of three stamp distributors from gallows outside the Town House. Before long, the demonstration spun out of control and the crowd attacked the homes of the distributors; the home of one, Martin Howard, was ransacked three separate times that night, and the home of another, Thomas Moffat, was struck twice. Both houses were little more than burnt-out shells by the following morning. Another official, George Meserve, arrived in Boston harbor to take up his appointment as stamp distributor of New Hampshire. He was greeted on the deck of his ship by a Bostonian pilot who warned him to resign before stepping onshore, for his own safety. Meserve took the pilot’s advice and resigned his commission before disembarking, at which point he was cheered by the same mob that had been on the verge of attacking him. Similarly, stamp distributors in New York, North Carolina, and Georgia resigned their commissions rather than face the wrath of colonial mobs.

In London, meanwhile, concerns about the effectiveness of the Stamp Act arose, especially after news of the American street violence made its way to Parliament. Trade with the colonies was also in decline because of merchants boycotting British goods as a protest to the Sugar Act; this led British merchants to lobby for the repeal of both Sugar and Stamp acts to return to business as usual. The most prominent supporter of the Stamp Act, George Grenville himself, had been dismissed from office on 10 July 1765, and was replaced as prime minister by Lord Rockingham. Though Grenville remained in Parliament, the case for keeping the Stamp Act in effect had weakened with his dismissal.

Love History?Sign up for our free weekly email newsletter!

When Parliament convened in December 1765, the Stamp Act was the main point of contention. George III gave the opening address, in which he spoke of the situation in America but did not reveal the extent of the resistance. After the speech, Grenville rose and proposed an amendment that would condemn colonial defiance of the Stamp Act. This amendment was ultimately rejected, but support for the Stamp Act remained firm amongst Grenville’s supporters, who argued that repealing the act would set a dangerous precedent. As the session adjourned for the New Year, the London merchants began working with Rockingham’s ministry to devise a strategy of repeal.

When Parliament reconvened on 14 January 1766, Rockingham formally proposed such a repeal. Petitions were read from merchants across Britain, who complained that the act had made it difficult for them to collect American debts which in turn was causing economic hardships throughout the country. On 7 February, a resolution was proposed by Grenville’s followers that the House of Commons would pledge to back the king in support of the Act; this resolution was defeated, prompting Grenville to accuse Parliament of sacrificing Britain’s sovereignty to placate the colonies. From 11-13 February, the House of Commons heard testimony from witnesses including Benjamin Franklin himself, who assured Parliament that Americans wanted nothing more than “to indulge in the fashions and manufactures of Great Britain” (Middlekauff, 120).

On 21 February, a resolution was introduced to repeal the Stamp Act. This was passed by a vote of 276 to 168. On 18 March 1766, George III gave his approval, and the Stamp Act was no more. However, along with the Repeal bill, Parliament passed the Declaratory Act, which stipulated that Parliament had the power to make binding laws in the American colonies “in all cases whatsoever”, which many interpreted to include taxation (Middlekauff, 118). Because of this, Parliament would impose further taxes on the colonies, known as the Townshend Acts, which would lead to further resistance. Therefore, the passage of the Stamp Act, and the fierce colonial resistance against it, marked an important turning point in Britain’s relationship with its North American colonies and helped spark the American Revolution.