I'd like to introduce the 2022 State of Trade on behalf of the Government of Canada.

This report highlights Canada's robust trade and investment recovery, which has displayed remarkable resilience during another challenging year. This year's report focuses on free trade agreements, which will continue to be vital tools for Canadian businesses as they enter this new phase of the post-pandemic recovery.

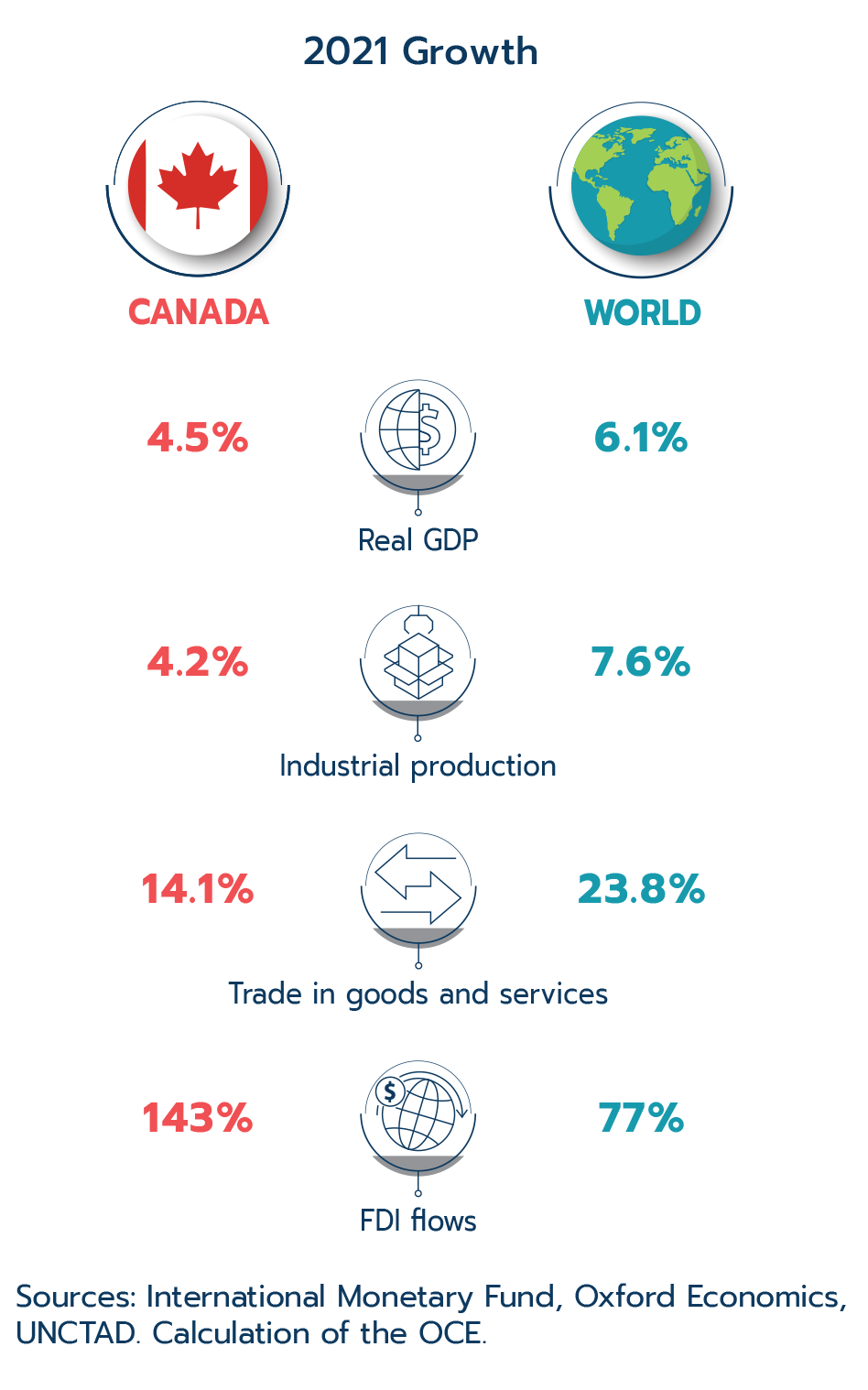

Last year was incredibly important for Canadians—it was a year of economic recovery amid a global pandemic. Businesses faced tremendous challenges, ranging from interrupted production and supply chain disruptions to rapid shifts in demand and elevated commodity prices. Despite significant challenges, Canada's two-way trade in goods and services rose 14.1% in 2021 to reach a new record high of $1.5 trillion; this is a testament to the adaptability and resilience of Canadian businesses, workers and entrepreneurs.

The scale of the government's emergency economic support helped to foster this strong recovery and enabled Canadians and businesses to better weather the pandemic. Budget 2022 pledged historic investments—in people, in the green transition and in innovation and productivity—to create jobs and prosperity and build a more robust economic future to support a stable and complete recovery.

Canada's free trade agreements (FTAs) are integral to solid business recovery. Canada is committed to enhancing this network by negotiating new FTAs with high-potential partners. FTAs support economic growth, open doors internationally, and facilitate the development of diversified and resilient supply chains. They also support the rules-based multilateral trading system. They have helped to keep markets open to allow access to food and medical supplies amid the unprecedented challenges of the past two years.

This year's State of Trade report details the impacts that FTAs have had on our economy—including their effects on exporters, workers, sustainability, and inclusiveness. Canada actively implements trade policies that maintain access to foreign markets for Canadian commerce while maximizing trade benefits for all Canadians.

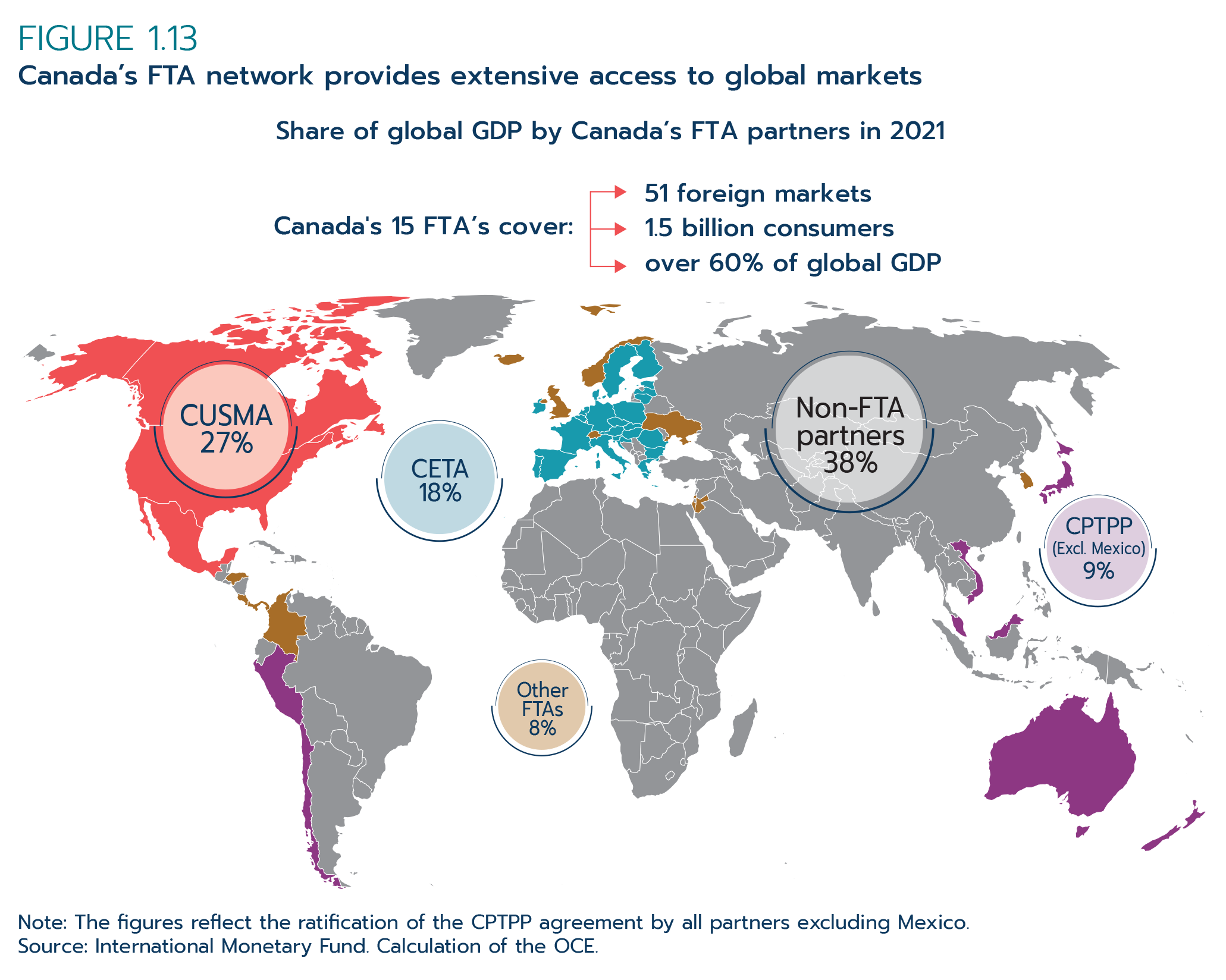

Canada is the only G7 economy with comprehensive free trade access to the entire G7 and European Union. Canada's 15 FTAs cover 61% of the world's GDP and open markets to 1.5 billion consumers worldwide. However, we recognize that opening doors is the first step in succeeding abroad. Our job is to help businesses take those next steps: from the Trade Commissioner Service to Export Development Canada, Canada's toolkit helps Canadian businesses start up, scale up, and access new markets.

As we move into the subsequent recovery phase, Canadian businesses and exporters will need to be as nimble as ever. I am confident that they are up to the challenge.

-The Honourable Mary Ng, Minister of International Trade, Export Promotion, Small Business and Economic Development

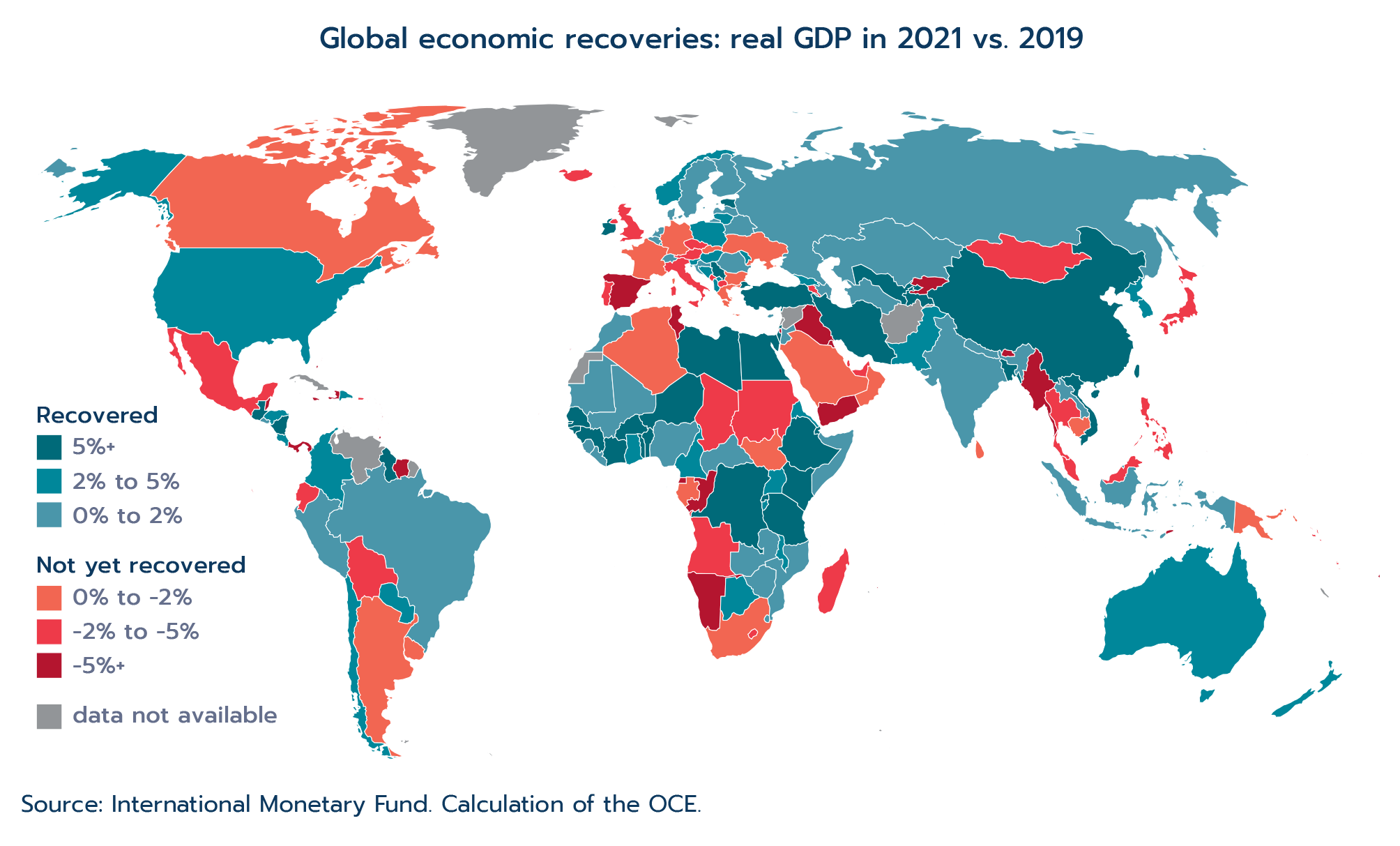

Canada is experiencing an economic recovery while still contending with a global pandemic. The world faced numerous challenges throughout 2021, including multiple waves of COVID-19, pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions and travel restrictions, and uneven vaccine access. Yet global GDP grew 6.1% in 2021 on the heels of a 3.1% contraction in 2020, as economies continued to reopen and production got back on track. However, beneath the surface of this strong growth, many countries struggled to recover from 2020 lows, and economic activity in almost half of all countries was actually lower in 2021 compared to their pre-pandemic 2019 levels.

Canada is also among that group, with last year's GDP coming in 0.9% below 2019 levels, even though Canada actually fared quite well relative to other advanced economies. The only G7 country that was further along in its recovery path was the U.S., with its economic activity 2.1% above 2019 levels. Canada had a strong labour market recovery, with an unemployment rate of only 6.0% by year-end. Many sectors such as finance, real estate, and retail trade thrived, while others, namely those in arts and recreation, accommodation and food struggled due largely to the effects of the pandemic and tight labour markets. Overall, the Canadian economy expanded 4.5% in 2021, following a 5.2% decline the year before.

The surge in activity south of Canada's border helped to drive record-breaking growth in Canadian trade. In 2021, exports of goods and services expanded 18.3% to reach a record high of $766 billion—driven largely by surging natural resources prices, but also from broad-based demand for a multitude of products, from consumer electronics to professional and financial services. Imports of goods and services surged 10.2% to $764 billion on the strength of pharmaceutical and medicinal products as well as imports of a variety of manufactured products. Canada's trade in goods overall enjoyed strong demand in 2021, while services overall had only begun to recover from the pandemic's devastating hit.

Unsurprisingly, Canada's robust trade can largely be credited to the U.S.'s strong economic recovery. Canada's exports of goods and services to the U.S. ballooned by 23.9% (reaching a record $550 billion), and imports grew 9.7% (to $463 billion). Much of this export growth was driven by demand for Canadian natural resources (especially energy products), as well as commercial services. Canada's trade with other countries also experienced notable growth, particularly in exports of goods, which expanded 21.9% overall, with positive growth in 8 out of Canada's top 10 trade partners. Meanwhile, services exports grew only 3.3% overall in 2021 with the recovery only gaining momentum toward the end of the year following the devastating 15.9% drop in 2020.

There was a solid recovery in both Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) and inward foreign direct investment (FDI) in 2021, as investment flows increased around the world. Unlike the slow recovery following the 2007-08 global financial crisis, investment flows rebounded quickly in 2021, with both CDIA and FDI surpassing their pre-pandemic levels.

Looking ahead, Canadian companies will continue to face headwinds. Russia's invasion of Ukraine injected fresh uncertainty, exacerbating already high inflation and putting additional pressure on supply chains. An important tool to support Canada's economic recovery is its vast network of free trade agreements (FTAs) that covers 61% of the world's GDP in 51 countries and opens doors to 1.5 billion consumers. This State of Trade report features Canada's FTAs and the benefits they bring to Canadians.

The merits of free trade are well known and include innovation, economies of scale, market competition, and increased access to products, to name a few. This report examines the impacts of FTAs after they have been put in place and the lessons learned from these past experiences.

Canada’s embrace of free trade dates back to the 1850s and 1860s, when Canada was part of British North America. However, all 15 of Canada’s current FTAs were put in place during the last 25 years.

A graphic depicts a timeline that starts at 1850 and runs until 2021. The years that Canada’s FTAs came into force are indicated along the timeline.

Canada's free trade agreement timeline

| Year | FTA put into force |

|---|---|

| 1854 | Reciprocity treaty with the United States |

| 1911 | Free trade initiative launched with the U.S., later abandoned |

| 1989 | CUSFTA |

| 1994 | NAFTA |

| 1997 | Israel |

| 1997 | Chile |

| 2002 | Costa Rica |

| 2009 | Peru |

| 2009 | EFTA |

| 2011 | Colombia |

| 2012 | Jordan |

| 2013 | Panama |

| 2014 | Honduras |

| 2015 | Korea |

| 2017 | CETA |

| 2017 | Ukraine |

| 2018 | CPTPP |

| 2020 | CUSMA |

| 2021 | United Kingdom |

Source: Global Affairs Canada.

Note: CUSFTA = Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement; NAFTA = North American Free Trade Agreement; EFTA = Canada-European Free Trade Association Free Trade Agreement; CETA = Canada-European Union Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement; CPTPP = Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership; CUSMA = Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement.

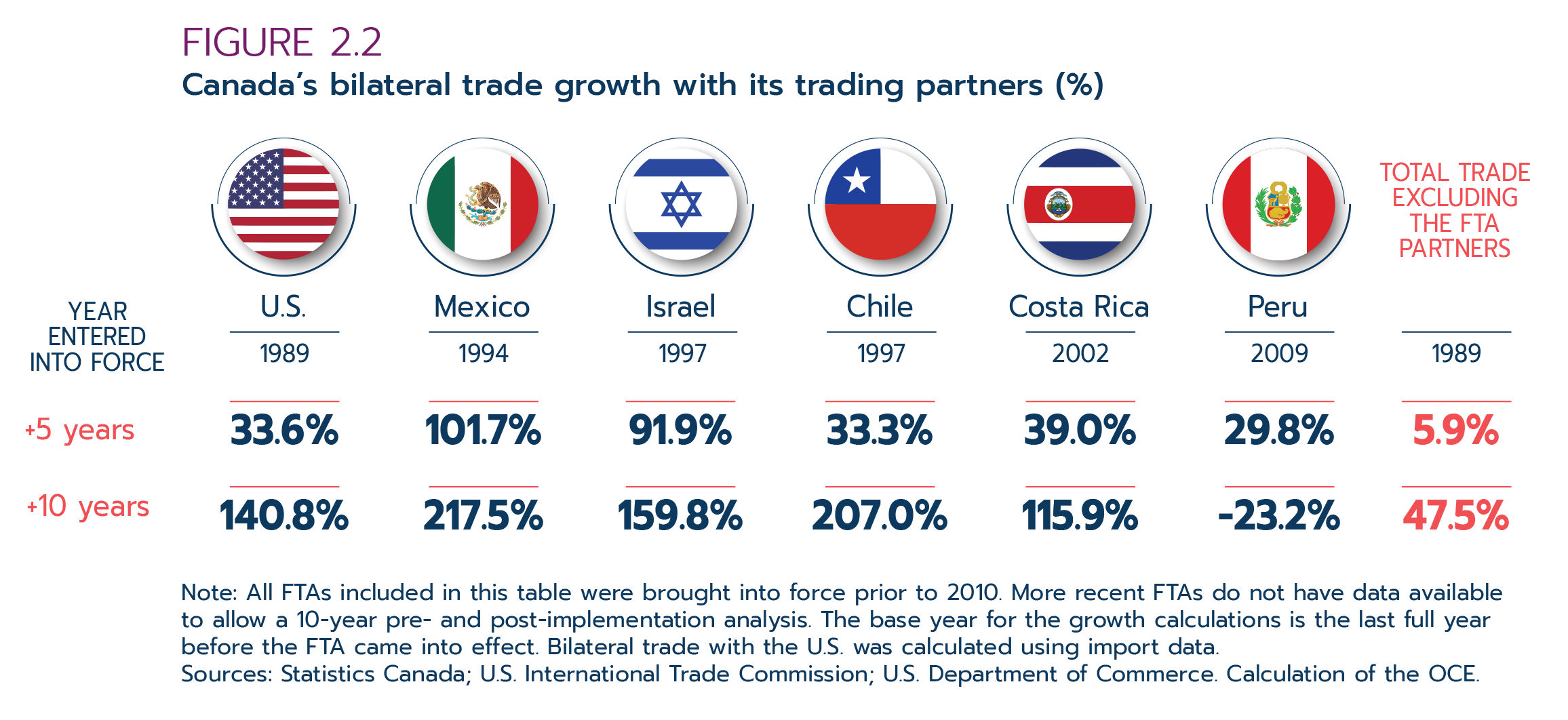

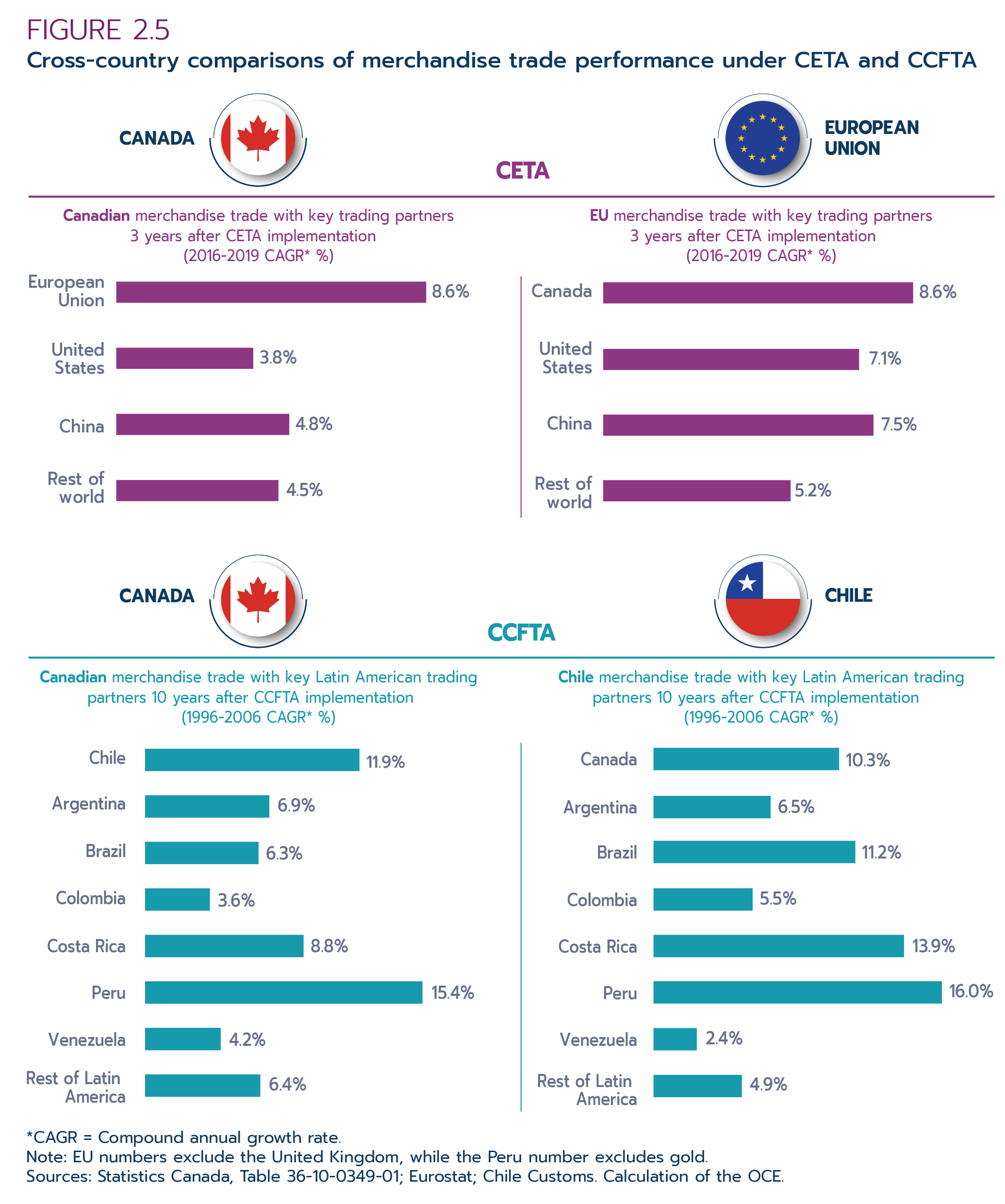

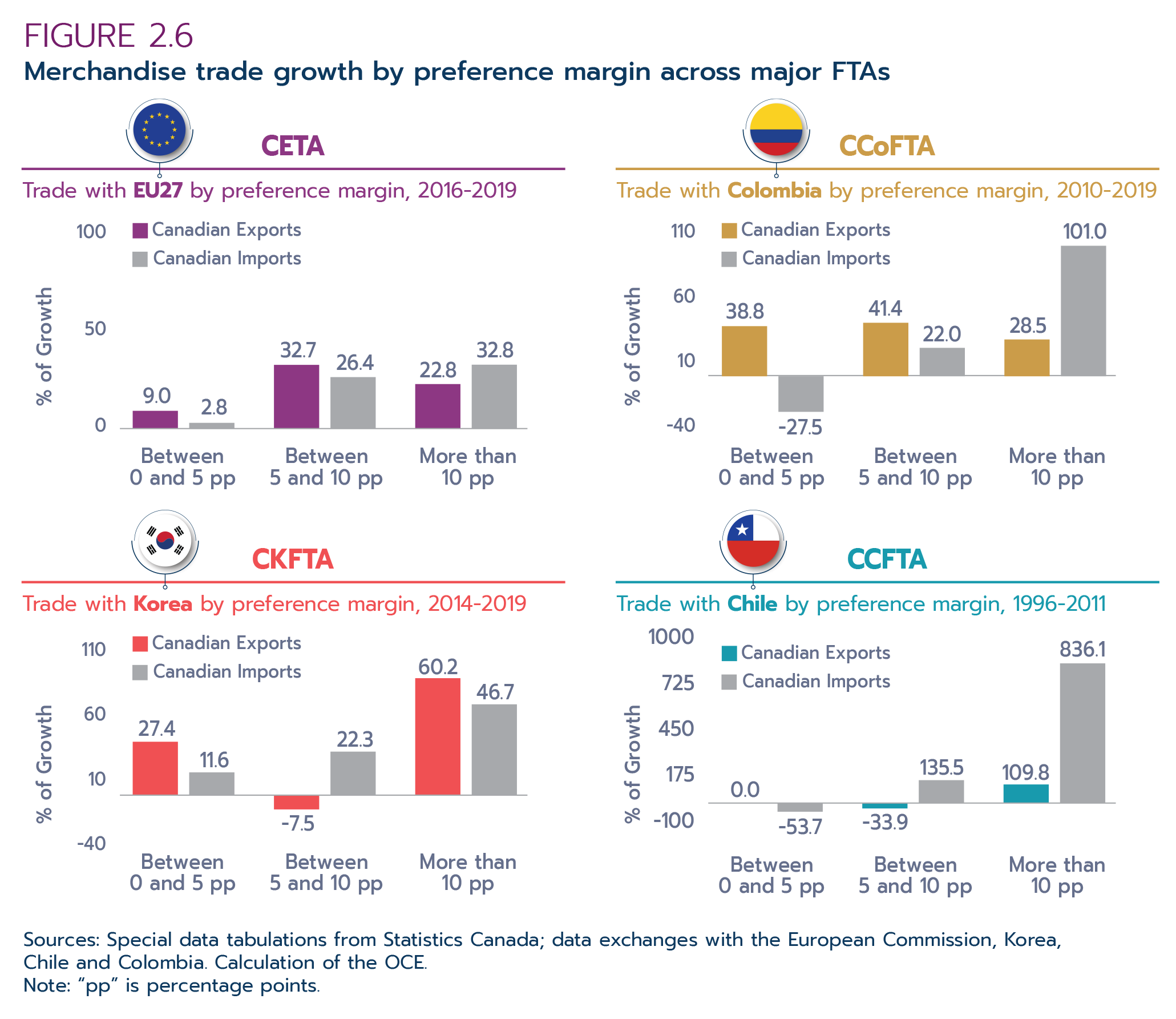

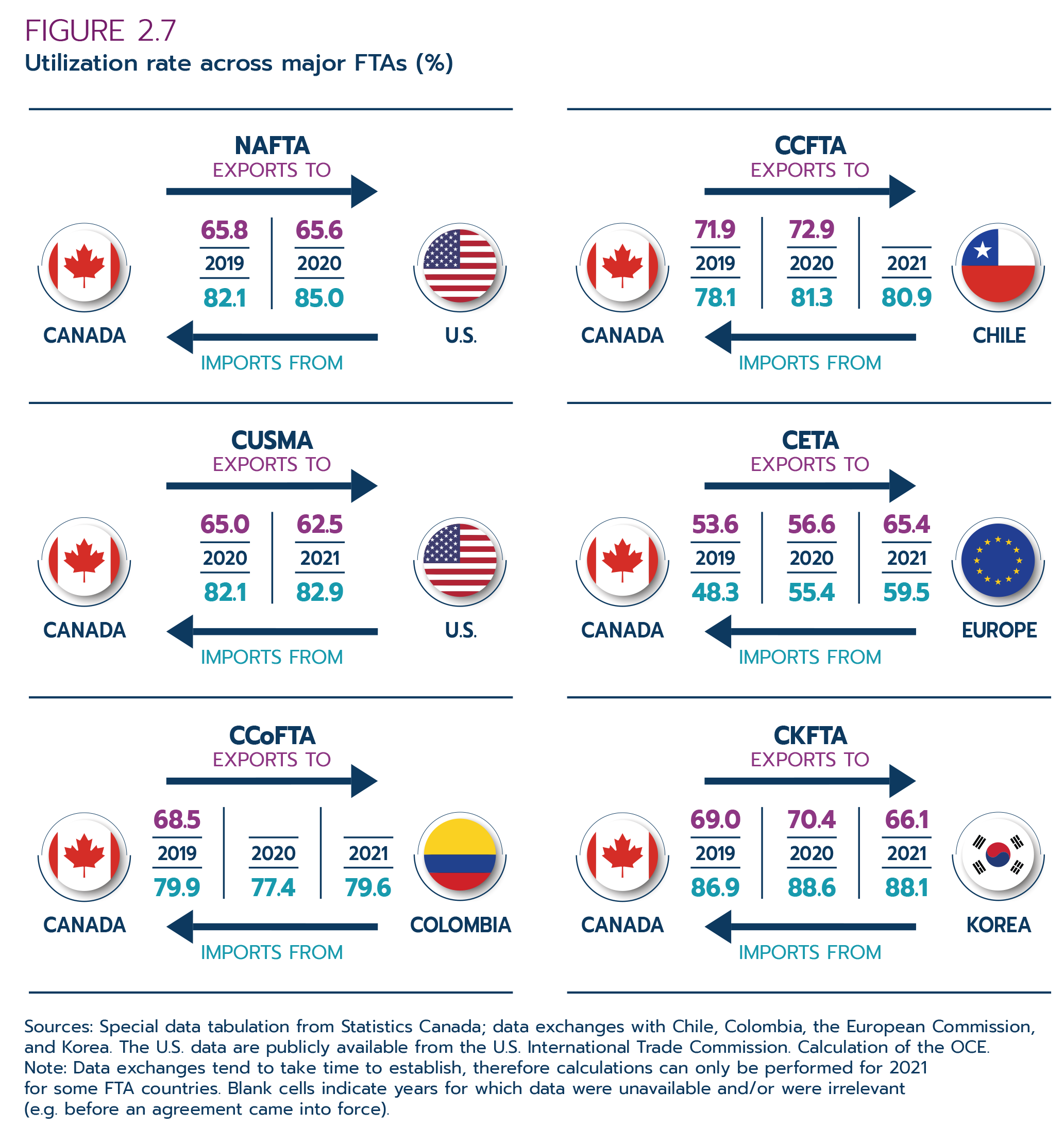

The raison d’être of FTAs is to augment trade among signatories to enhance the well-being of society in the long run. Bilateral trade more than doubled in the 10 years following the entry into force of Canada’s FTAs that were signed before 2010 (with the exception of Canada’s FTA with Peru). Moreover, Canadian companies tended to increase their use of tariff preferences in the years following implementation of FTAs. Our analysis of the 1997 Canada-Chile FTA established a causal link determining that the FTA increased bilateral trade 12.2% faster than would have been the case in the absence of the agreement. A similar analysis found that bilateral trade with Colombia increased on average 5.8% to 7.0% faster than it would have in the absence of the Canada-Colombia FTA signed in 2011.

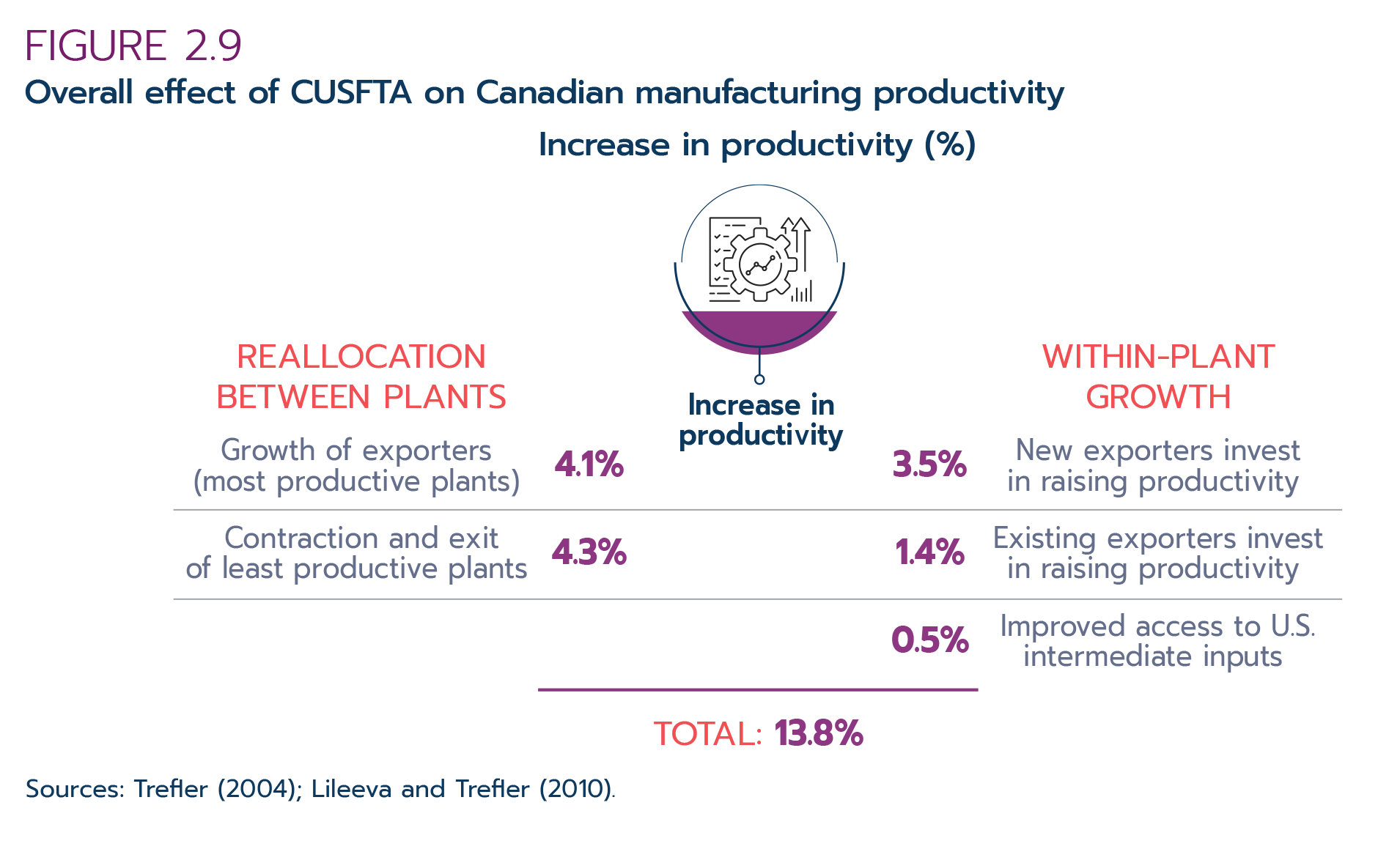

While increased trade is the immediate objective of FTAs, the ultimate objective is to enhance the overall well-being—or welfare—of society. This welfare benefit is measured through producer and consumer gains; the analysis is important because FTAs do not guarantee an optimal welfare outcome. Producers can benefit from efficiency gains; for example, the labour productivity of Canadian manufacturing plants increased following the 1989 Canada-United States FTA, and exporting firms were on average more productive than non-exporting firms following the FTA. Meanwhile, consumers benefit from an increased variety of products at lower prices.

Free trade might boost national welfare on the whole, but there is no guarantee that all people will be better off. Therefore, trade agreements need to be appropriately designed to ensure that all segments of society can benefit from the opportunities that flow from free trade. Research regarding the effects of China’s accession to the World Trade Organization has demonstrated that the adjustment can be quite slow and painful for many workers; however, it’s important to recognize the consumer benefits that stem from the increased access as well as increased export opportunities.

Increased trade between developed countries has been found to have a limited impact on labour market outcomes. In the context of the 1989 Canada-United States FTA, there was no evidence that workers were permanently pushed out of the labour force, even in industries with significant tariff reductions; there were high levels of re-employment in other manufacturing industries or even other firms within the same industry. Perhaps more importantly, decreases in income in the short run were offset by higher earnings in the longer term.

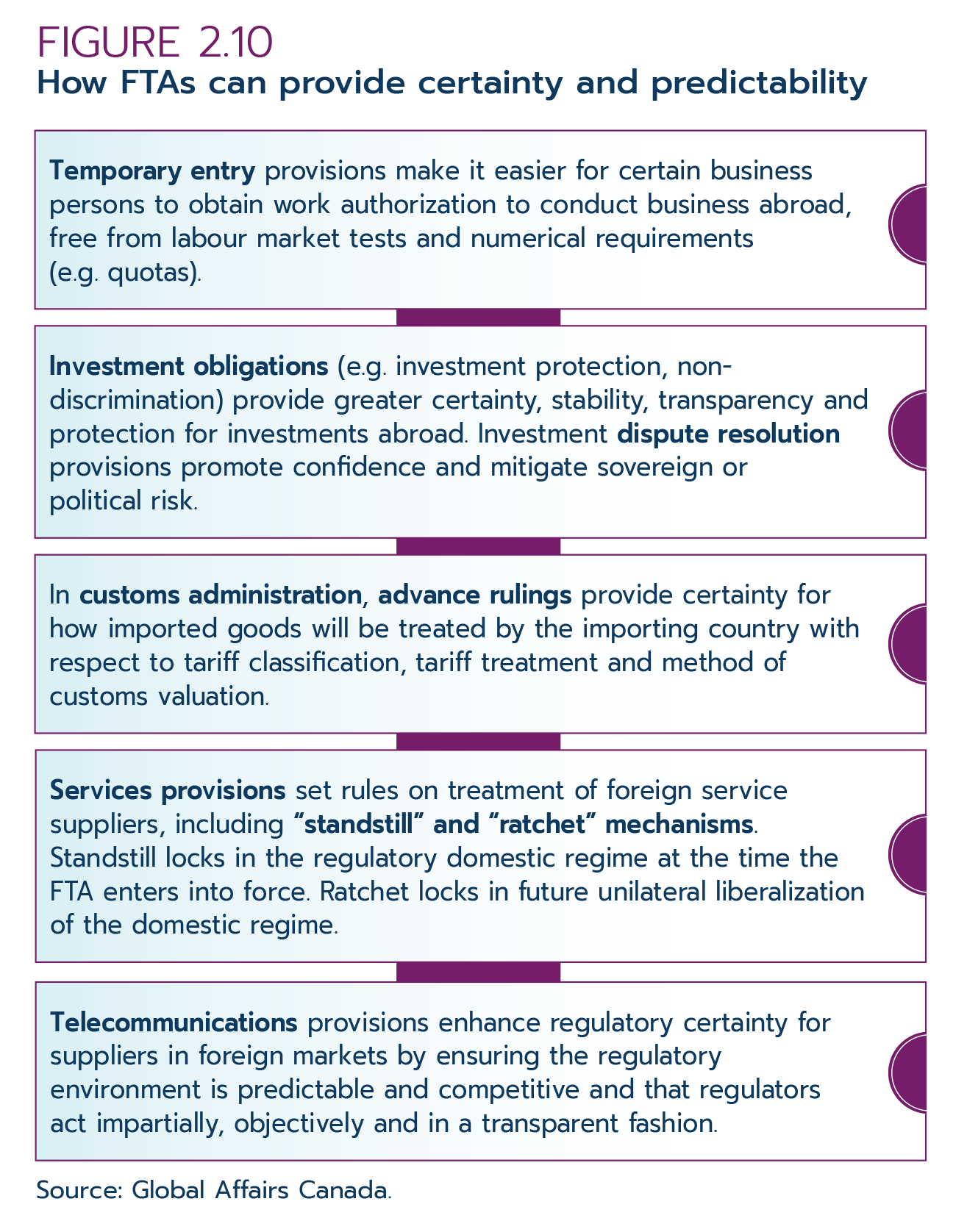

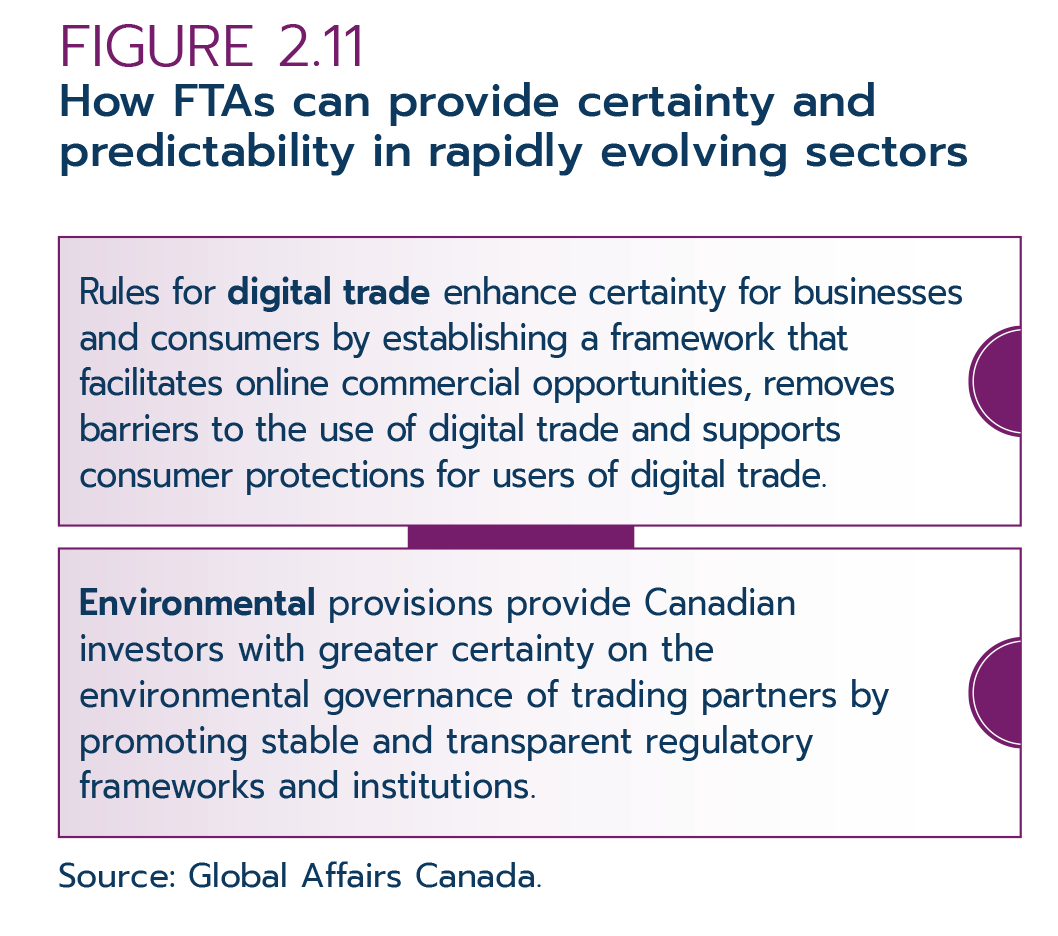

With tariffs around the world now at near historical lows, there are other commitments that are gaining prominence in FTAs. These include commitments to reduce red tape, increase predictability in regulatory requirements, and commitments to broader goals such as addressing environmental issues and protecting human rights. Early evidence points to FTAs being effective at lowering these trade barriers and the overall costs of trade. Additionally, the design of FTAs can contribute to reducing the export of environmentally harmful goods and to increasing so-called “green” goods, particularly for developing countries.

FTAs can also have wider impacts on diplomatic relations, security and governance. In fact, FTAs are closely tied to increases in other types of agreements, including those on investment, infrastructure and transportation, and have even resulted in common voting patterns at the United Nations. Moreover, increased trade between countries with FTAs has been found to significantly reduce the likelihood of conflict between them by increasing the cost of conflict, providing resolution mechanisms and enhancing the familiarity with respective institutions.

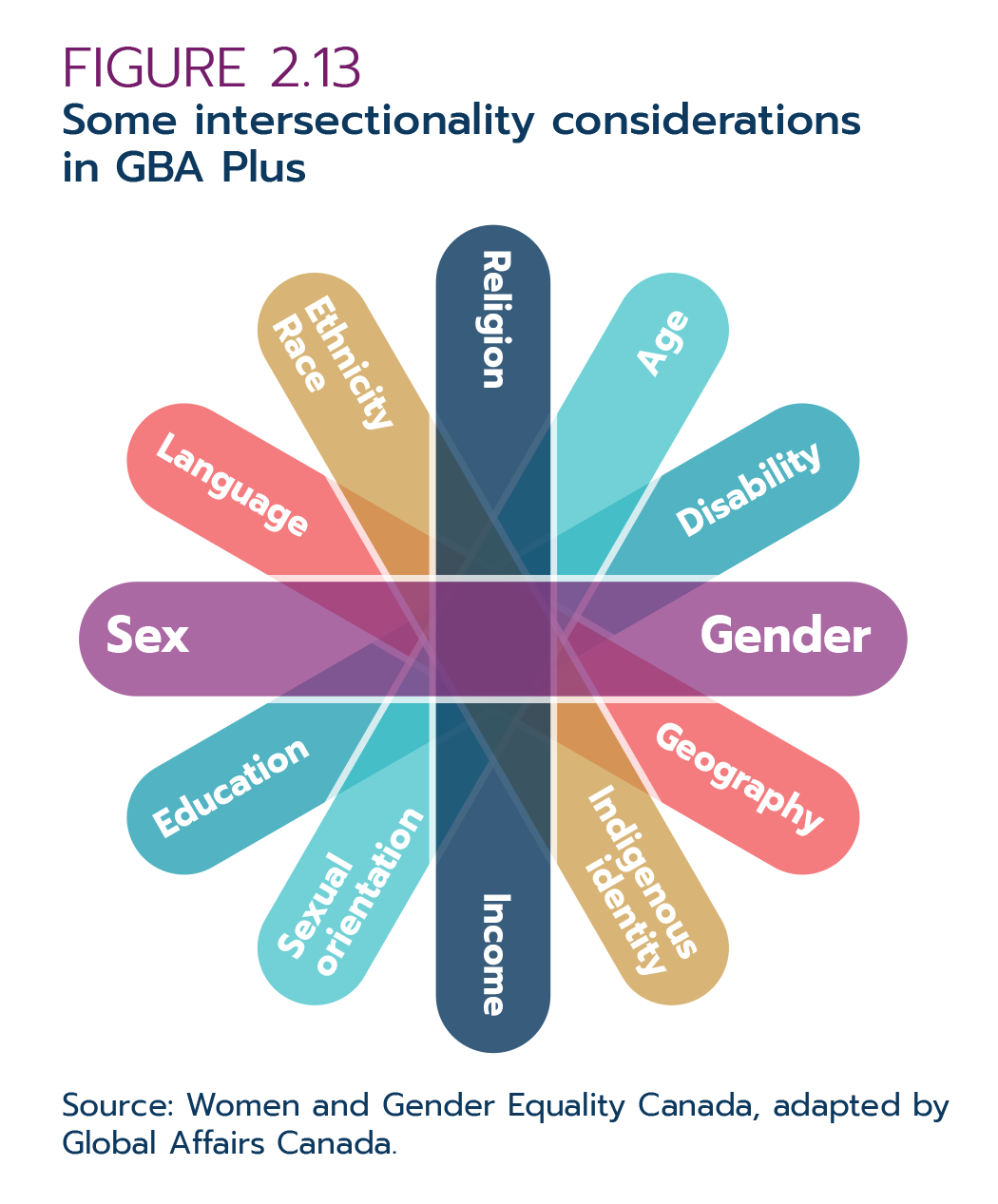

As part of the trade diversification agenda, Canada is implementing its inclusive approach to trade. Canada’s approach aims to ensure that the benefits and opportunities that flow from trade are more widely shared, including with equity deserving groups such as women, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), and Indigenous peoples. This involves seeking gender responsive and inclusive provisions across FTAs, supported by gender-based analysis (GBA Plus), and standalone chapters on trade and gender, SMEs, and trade and Indigenous peoples.

FTAs have a broad range of impacts, including significant positive effects that go beyond immediate economic outcomes. Understanding these impacts can help negotiators tailor future FTAs to maximize their positive effects, address fast-evolving phenomena such as the digital economy and confront other issues as they arise.

Key data

2021 Growth

| Real GDP | Industrial production | Trade in goods and services | FDI flows | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Canada | 4.5% | 4.2% | 14.1% | 143% |

| World | 6.1% | 7.6% | 23.8% | 77% |

Sources: Statistics Canada, International Monetary Fund, Oxford Economics, UNCTAD. Calculation of the OCE.

It has been over 2 years since the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has provoked profound impacts on the global and Canadian economies and disrupted almost every aspect of our daily lives. As 2021 began, the world was already on the path to recovery, albeit an uncertain one. Many countries entered the new year in a weaker position than expected due to unforeseen setbacks such as the emergence of new variants leading to renewed public health restrictions, supply chain disruptions delaying production, and supply and demand imbalances leading to surging prices. As the year went on, and vaccination programs were rolled out, people became more and more optimistic, and the recovery became a little more stable.

However, even amid the optimism, the latter part of 2021 brought forth additional challenges for people and businesses with further supply chain issues and public health concerns, all of which reduced the strength of the recovery. Moreover, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in early 2022 has introduced new challenges around the world and has threatened the rules-based international order. In Part 1 of State of Trade 2022, we will look back at the past year to see how the global and Canadian economies have fared since the historical crash in 2020.

Key data

A heat map classifies each country in the world into 1 of 6 categories in terms of their stage of economic recovery, each represented by a colour. The first 3 categories represent countries that had 2021 GDP higher than 2019, and are represented by shades of teal, with the darkest shade being the most recovered. The next 3 categories represent countries that had 2021 GDP lower than 2019 and are represented by shades of red, with the darkest shade being the least recovered.

Recovered (2021 GDP > 2019 GDP)

| % difference in 2021 vs. 2019 GDP | Category | Shade |

|---|---|---|

| 5%+ | 1 | Darkest teal |

| 2% to 5% | 2 | Middle teal |

| 0% to 2% | 3 | Lightest teal |

Not yet recovered (2021 GDP < 2019 GDP)

| % difference in 2021 vs. 2019 GDP | Category | Shade |

|---|---|---|

| 0% to -2% | 4 | Lightest red |

| -2% to -5% | 5 | Middle red |

| -5%+ | 6 | Darkest red |

The colour grey represents countries where data were not available.

Global economic recoveries: 2021 vs. 2019 real GDP

| Territory | GDP recovery category |

|---|---|

| Afghanistan | data not available |

| Albania | 2 |

| Algeria | 4 |

| Andorra | 5 |

| Angola | 5 |

| Antigua and Barbuda | 6 |

| Argentina | 4 |

| Armenia | 5 |

| Aruba | 6 |

| Australia | 2 |

| Austria | 5 |

| Azerbaijan | 3 |

| Bahamas | 6 |

| Bahrain | 5 |

| Bangladesh | 1 |

| Barbados | 6 |

| Belarus | 3 |

| Belgium | 3 |

| Belize | 6 |

| Benin | 1 |

| Bhutan | 6 |

| Bolivia | 5 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina | 2 |

| Botswana | 2 |

| Brazil | 3 |

| Brunei Darussalam | 3 |

| Bulgaria | 4 |

| Burkina Faso | 1 |

| Burundi | 2 |

| Cabo Verde | 6 |

| Cambodia | 4 |

| Cameroon | 2 |

| Canada | 4 |

| Central African Republic | 3 |

| Chad | 5 |

| Chile | 2 |

| China | 1 |

| Colombia | 2 |

| Comoros | 3 |

| Democratic Republic of the Congo | 1 |

| Congo | 6 |

| Costa Rica | 2 |

| Côte d'Ivoire | 1 |

| Croatia | 3 |

| Cyprus | 3 |

| Czech Republic | 5 |

| Denmark | 3 |

| Djibouti | 1 |

| Dominica | 6 |

| Dominican Republic | 2 |

| Ecuador | 5 |

| Egypt | 1 |

| El Salvador | 3 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 6 |

| Eritrea | 2 |

| Estonia | 1 |

| Eswatini | 3 |

| Ethiopia | 1 |

| Fiji | 6 |

| Finland | 3 |

| France | 4 |

| Gabon | 4 |

| The Gambia | 1 |

| Georgia | 2 |

| Germany | 4 |

| Ghana | 2 |

| Greece | 4 |

| Grenada | 6 |

| Guatemala | 1 |

| Guinea | 1 |

| Guinea-Bissau | 1 |

| Guyana | 1 |

| Haiti | 6 |

| Honduras | 2 |

| Hong Kong | 4 |

| Hungary | 2 |

| Iceland | 5 |

| India | 3 |

| Indonesia | 3 |

| Iran | 1 |

| Iraq | 6 |

| Ireland | 1 |

| Israel | 1 |

| Italy | 5 |

| Jamaica | 6 |

| Japan | 5 |

| Jordan | 3 |

| Kazakhstan | 3 |

| Kenya | 1 |

| Kiribati | 3 |

| Korea | 2 |

| Kosovo | 2 |

| Kuwait | 6 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 6 |

| Laos | 3 |

| Latvia | 3 |

| Lebanon | data not available |

| Lesotho | 5 |

| Liberia | 3 |

| Libya | 1 |

| Lithuania | 2 |

| Luxembourg | 2 |

| Macedonia | 5 |

| Macao | 6 |

| Madagascar | 5 |

| Malawi | 2 |

| Malaysia | 5 |

| Maldives | 6 |

| Mali | 3 |

| Malta | 3 |

| Marshall Islands | 5 |

| Mauritania | 3 |

| Mauritius | 6 |

| Mexico | 5 |

| Micronesia | 6 |

| Moldova | 2 |

| Mongolia | 5 |

| Montenegro | 5 |

| Morocco | 3 |

| Mozambique | 3 |

| Myanmar | 6 |

| Namibia | 6 |

| Nauru | 2 |

| Nepal | 3 |

| Netherlands | 3 |

| New Zealand | 2 |

| Nicaragua | 1 |

| Niger | 1 |

| Nigeria | 3 |

| Norway | 2 |

| Oman | 4 |

| Pakistan | 2 |

| Palau | 6 |

| Panama | 6 |

| Papua New Guinea | 4 |

| Paraguay | 2 |

| Peru | 3 |

| Philippines | 5 |

| Poland | 2 |

| Portugal | 5 |

| Puerto Rico | 5 |

| Qatar | 5 |

| Romania | 3 |

| Russia | 3 |

| Rwanda | 1 |

| Samoa | 6 |

| San Marino | 4 |

| São Tomé and Príncipe | 2 |

| Saudi Arabia | 4 |

| Senegal | 1 |

| Serbia | 1 |

| Seychelles | 4 |

| Sierra Leone | 3 |

| Singapore | 2 |

| Slovakia | 4 |

| Slovenia | 2 |

| Solomon Islands | 5 |

| Somalia | 3 |

| South Africa | 4 |

| South Sudan | 4 |

| Spain | 6 |

| Sri Lanka | 4 |

| St. Kitts and Nevis | 6 |

| St. Lucia | 6 |

| St. Vincent and the Grenadines | 6 |

| Sudan | 5 |

| Suriname | 6 |

| Sweden | 3 |

| Switzerland | 3 |

| Syria | data not available |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| Tajikistan | 1 |

| Tanzania | 1 |

| Thailand | 5 |

| Timor-Leste | 6 |

| Togo | 1 |

| Tonga | 4 |

| Trinidad and Tobago | 6 |

| Tunisia | 6 |

| Turkey | 1 |

| Turkmenistan | 3 |

| Tuvalu | 2 |

| Uganda | 2 |

| Ukraine | 4 |

| United Arab Emirates | 5 |

| United Kingdom | 5 |

| United States | 2 |

| Uruguay | 4 |

| Uzbekistan | 1 |

| Vanuatu | 5 |

| Venezuela | data not available |

| Vietnam | 1 |

| West Bank and Gaza | 6 |

| Yemen | 6 |

| Zambia | 3 |

| Zimbabwe | 3 |

Source: International Monetary Fund. Calculation of the OCE.

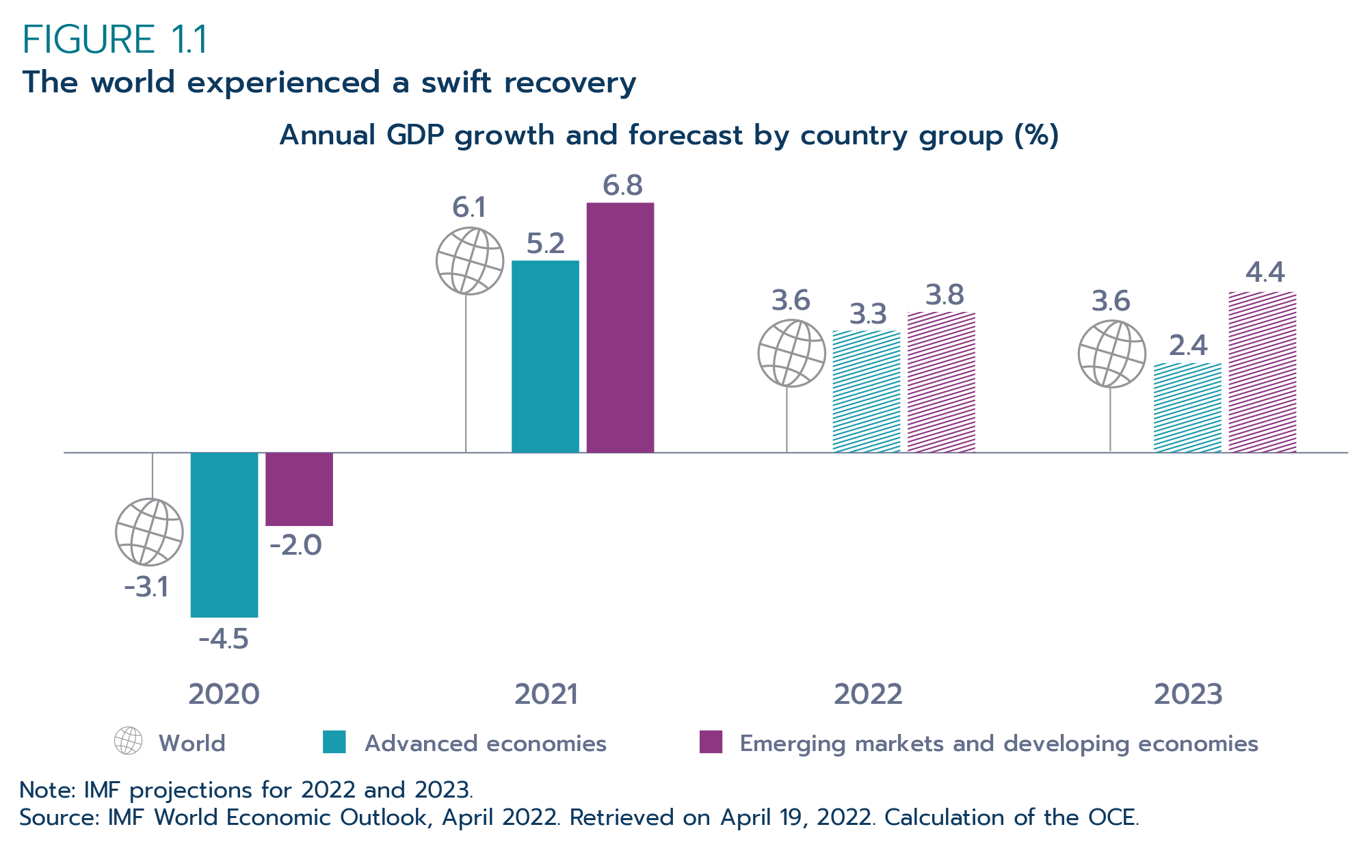

Overall, the world posted a robust economic recovery for 2021. According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), world real GDP rebounded by 6.1% in 2021 after a 3.1% decline in 2020 (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: The world experienced a swift recovery

Annual real GDP growth and projection by country group (%)

| 2020 | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| World | -3.1 | 6.1 | 3.6 | 3.6 |

| Advanced economies | -4.5 | 5.2 | 3.3 | 2.4 |

| Emerging markets and developing economies | -2.0 | 6.8 | 3.8 | 4.4 |

Note: IMF projections for 2022 and 2023.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2022. Retrieved on April 19, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

However, while growth surpassed the IMF’s October forecast by 0.2 percentage points, there was a slowdown in economic activity around the world in the second half of the year. One of the key reasons for the slowdown was a prolonged disruption to global supply chains, as high seaborne freight costs, congested ports, and shortages of key products showed few signs of improvement by the end of the year. This, coupled with uneven rollout of vaccines in some countries, restrained global economic activity. Furthermore, despite high vaccine uptake in advanced economies, the emergence and spread of the Omicron variant during the final few weeks of 2021 led to a rapid deterioration of health conditions and consumer sentiment around the world. Lastly, in addition to these factors, broadening price pressures across regions (for example, energy and food prices) continued to build up throughout the second half of the year.

The United States was one of the countries most impacted by the global supply chain disruptions. Supply-side problems persisted throughout the year as container ships waited to unload off the coast of California and a global shortage of semiconductors hampered production in several industries, but primarily in motor vehicle manufacturing. The back up in warehousing, increased shipping rates, and supply and demand imbalances all contributed to a significant deceleration of U.S. economic growth in the third quarter of 2021. In China, the combined effects of resurgence in COVID-19 cases, electricity shortages constraining industrial production, and declining real estate investment also dampened the country’s economic growth. Similarly, in Europe, supply-side disruptions coupled with the later spread of the Omicron variant resulted in economic activity stalling among European countries in the last quarter of the year.

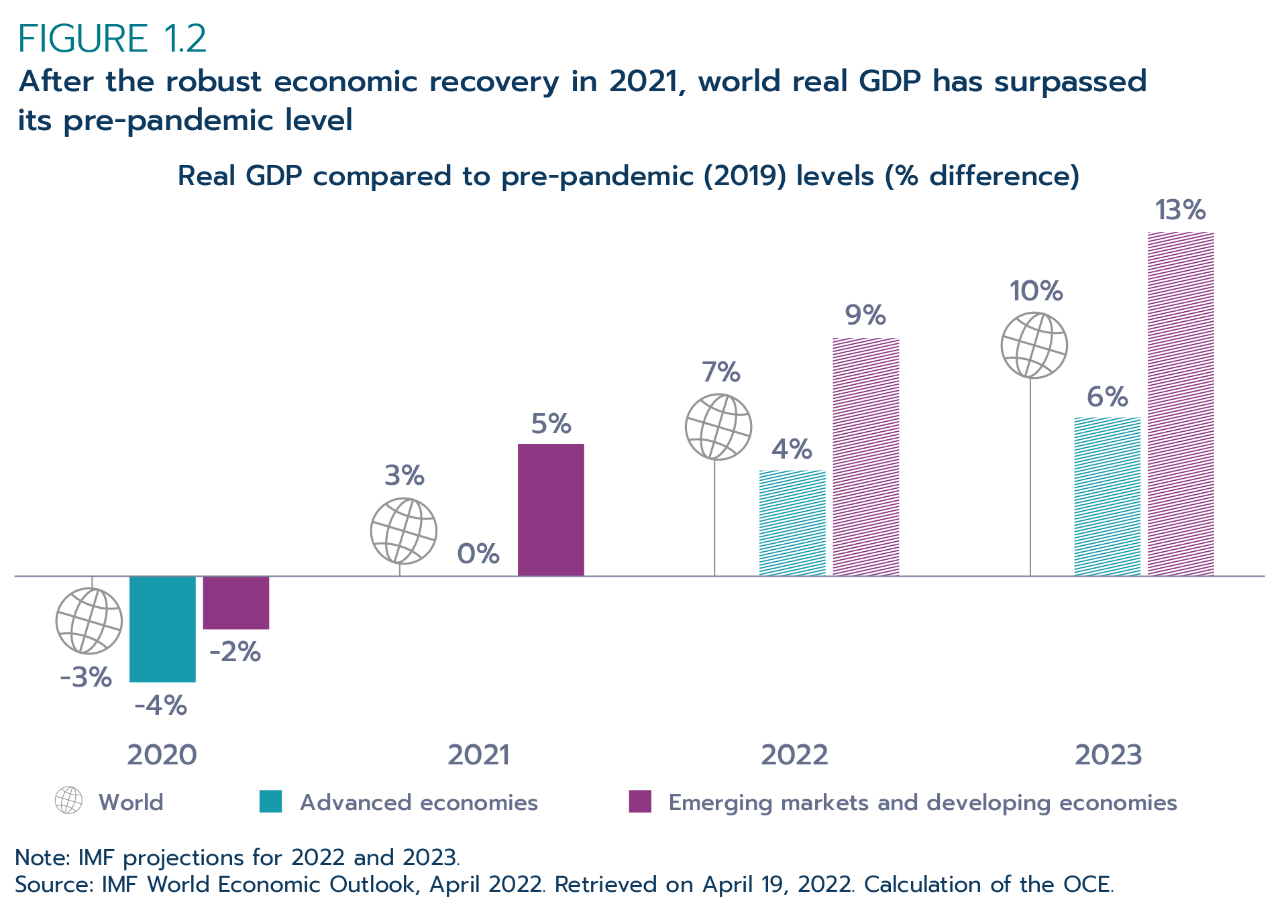

For 2021 overall, emerging markets (6.8% growth) outperformed advanced economies (5.2% growth). While significant uncertainties remain, this trend is currently expected to continue over the next 2 years, with emerging markets growing by 3.8% in 2022 and another 4.4% in 2023; meanwhile, advanced economies are projected to grow 3.3% in 2022 and 2.4% in 2023. In terms of real output levels, both groups of economies recovered their losses incurred in 2020 and surpassed their pre-pandemic 2019 levels by the end of 2021 (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2: After the robust economic recovery in 2021, world real GDP has surpassed its pre-pandemic level

Real GDP compared to pre-pandemic (2019) levels (% difference)

| World | Advanced economies | Emerging markets and developing economies | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | -3% | -4% | -2% |

| 2021 | 3% | 0% | 5% |

| 2022 | 7% | 4% | 9% |

| 2023 | 10% | 6% | 13% |

Note: IMF projections for 2022 and 2023.

Source: IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2022. Retrieved on April 19, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

Despite widespread supply chain issues such as the ongoing global semiconductor shortage and port backlogs weighing down on the pace of recovery, global merchandise trade posted historical growth in 2021. The resurgence of global economic activity in the first half of the year was the main factor driving global trade volumes above their pre-pandemic records. The World Trade Organization (WTO) estimated a 9.8% increase in world merchandise trade volume in 2021, followed by a projected 3.0% growth in 2022 (WTO, 2022). Compared to the pre-pandemic peak in 2019, 2021 world merchandise trade volume was also 4.3% higher. On the other hand, while the value of global trade in commercial services increased by 15% in 2021, many sectors, especially those that rely on face-to-face interactions, continued to lag behind goods trade.

Following a sharp decline in 2020 (-37%), global inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) rebounded quickly in 2021, estimated at US$1.7 trillion (UNCTAD, 2022). This represents a 77% increase from 2020, surpassing pre-pandemic levels by over US$150 billion. The recovery was faster than previously projected by UNCTAD (2020) and widespread across regions. Developed economies, which had experienced the largest pandemic-driven drop in FDI (-65%), saw their FDI inflows almost triple in 2021, to an estimated US$777 billion. In developing economies, where the 2020 decline was less severe (-7%), FDI inflows grew by 30% to US$870 billion in 2021 (UNCTAD, 2022). About one third of the increase in global FDI inflows in 2021 was driven by cross-border mergers and acquisitions (M&As) (UNCTAD, 2022). The surge in M&As was primarily in the services sector, which accounted for close to three quarters of cross-border M&A deals in 2021. In January, UNCTAD projected a positive outlook for 2022, with a slower growth than in 2021, as underlying trends were expected to remain unchanged.

The world contended with new challenges right into 2022. The global economy remains fragile, and further setbacks could affect Canada. A major new source of uncertainty was brought about by the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has led to the loss of thousands of lives and the exodus of millions of Ukrainians. This attack has put the supply of important commodities such as wheat and oil at risk and has resulted in a surge in commodity prices. The ramifications are being felt worldwide, weighing on markets and business confidence. In April, the IMF downgraded its 2022 global GDP forecast to 3.6% from its January forecast of 4.4%, and businesses and markets are expected to continue contending with these global challenges for some time.

Key data

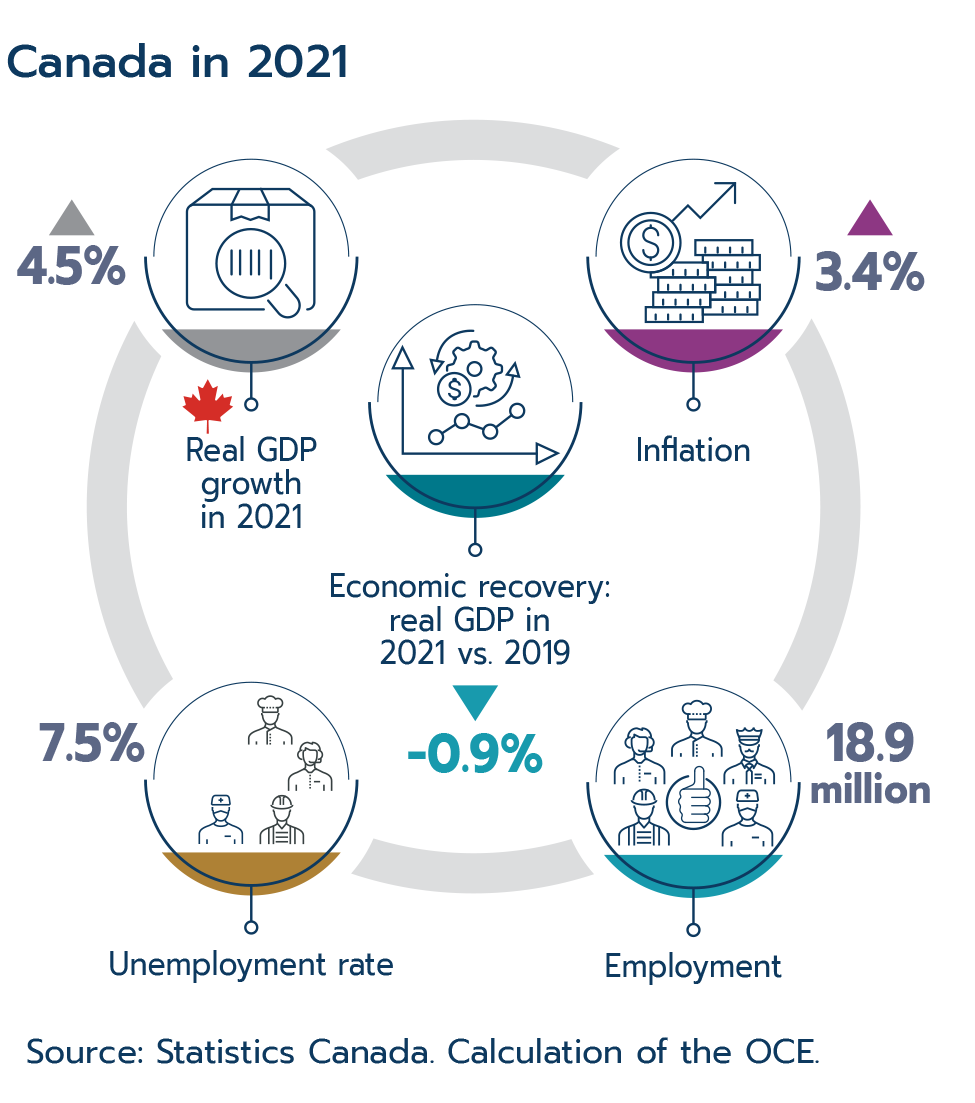

A diagram depicts 2021 economic statistics for the Canadian economy.

Canada in 2021

| Real GDP growth in 2021 | 4.5% |

| Inflation | 3.4% |

| Economic recovery: real GDP in 2021 vs. 2019 | -0.9% |

| Unemployment rate | 7.5% |

| Employment | 18.9 million |

Canada's economy rebounded strongly in 2021 (4.5%) after a historical contraction in the year prior (-5.2%). However, the Canadian economy experienced many challenges, starting with a fresh wave of COVID-19 cases and restrictions, which slowed economic recovery to 4.4% growth in the first quarter of 2021 on the heels of 9.1% growth in the last quarter of 2020 (seasonally adjusted at annual rates). On top of public health measures restricting economic activity, the second quarter of the year experienced a slowdown in the resale housing market and a decline in exports, which together led to a contraction in Canada's real GDP of 3.1%.

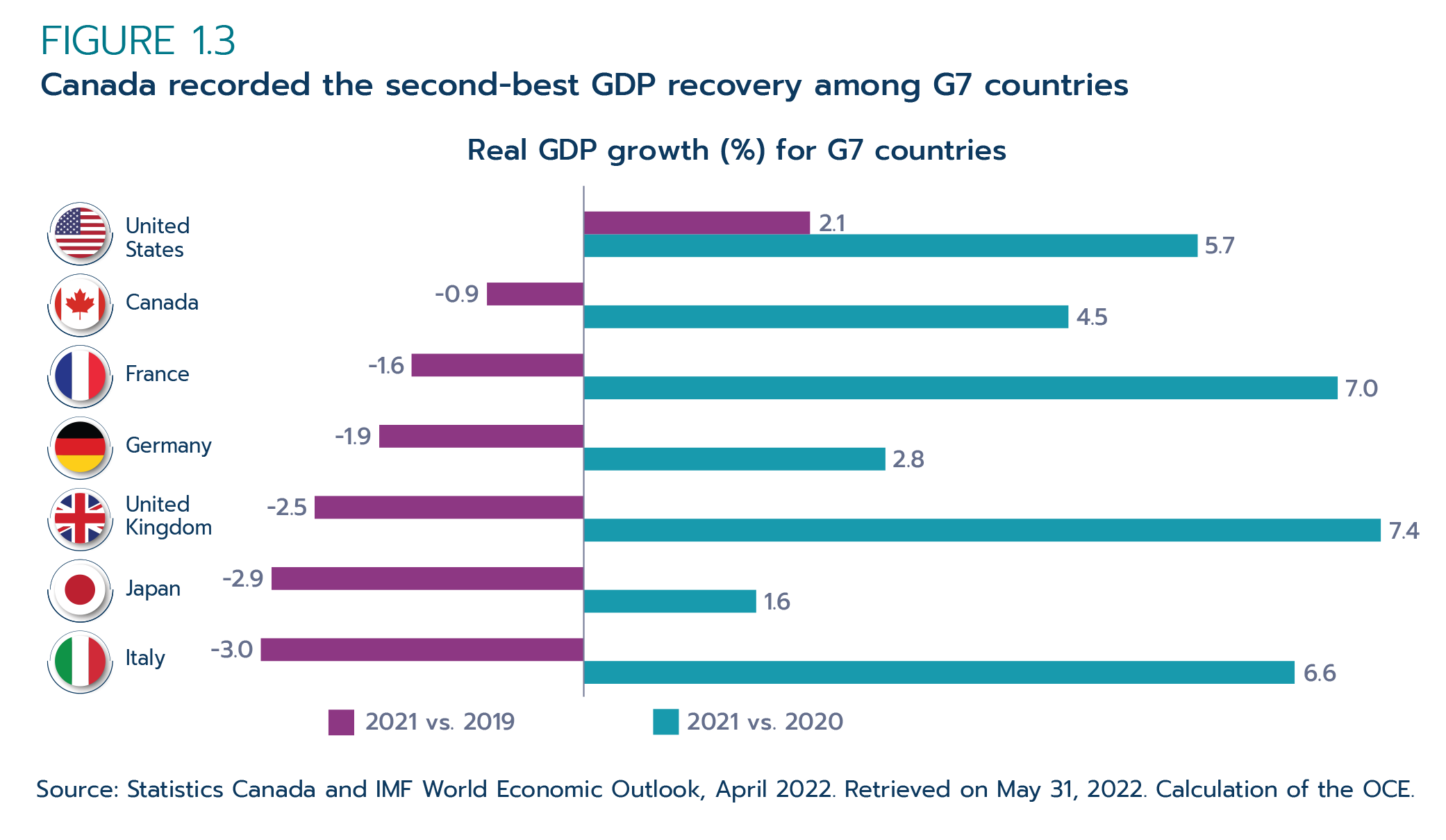

Fortunately, the economic recovery resumed in the second half of 2021. As public health restrictions eased, households increased their spending and exports turned around in the third quarter, leading to a 5.3% growth in overall economic activity. This momentum carried into the fourth quarter of 2021, which saw the economy expand by 6.6% on the back of business investment in engineering structures and home ownership transfer costs. For the full year, Canada's real GDP rose by 4.5%. Moreover, while Canada's 2021 GDP growth was slower than that of many of its G7 peers, it is in a better position than most in terms of the recovery. The U.S. economy had the strongest recovery, with 2021 GDP sitting 2.1% higher than it was in 2019. Canada had the second-strongest showing, with 2021 economic activity only 0.9% lower than in 2019 (Figure 1.3).

Figure 1.3: Canada recorded the second-best GDP recovery among G7 countries

Real GDP growth (%) for G7 countries

| Country | 2021 vs. 2020 | 2021 vs. 2019 |

|---|---|---|

| United States | 5.7 | 2.1 |

| Canada | 4.5 | -0.9 |

| France | 7.0 | -1.6 |

| Germany | 2.8 | -1.9 |

| United Kingdom | 7.4 | -2.5 |

| Japan | 1.6 | -2.9 |

| Italy | 6.6 | -3.0 |

Source: Statistics Canada and IMF World Economic Outlook, April 2022.

Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

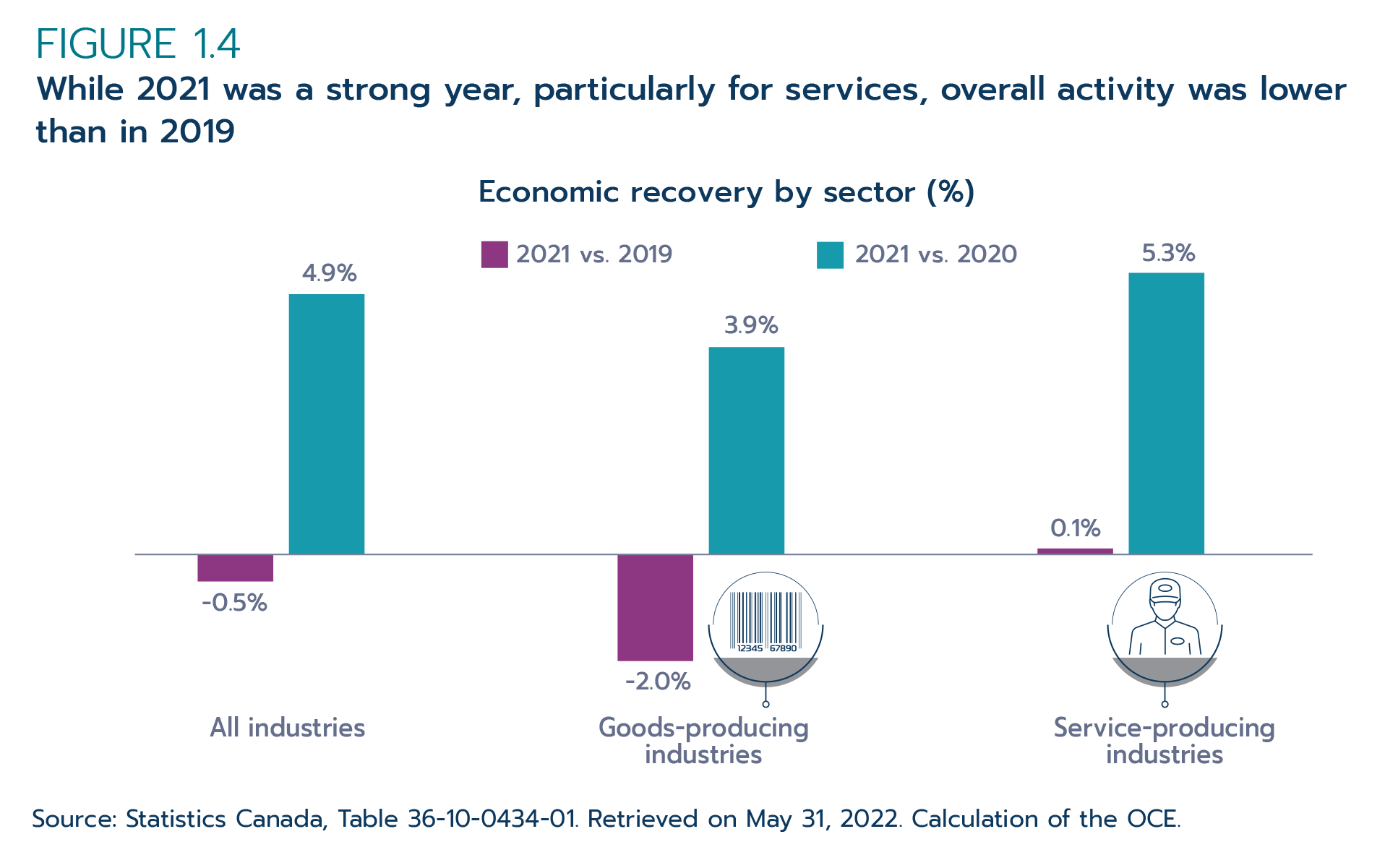

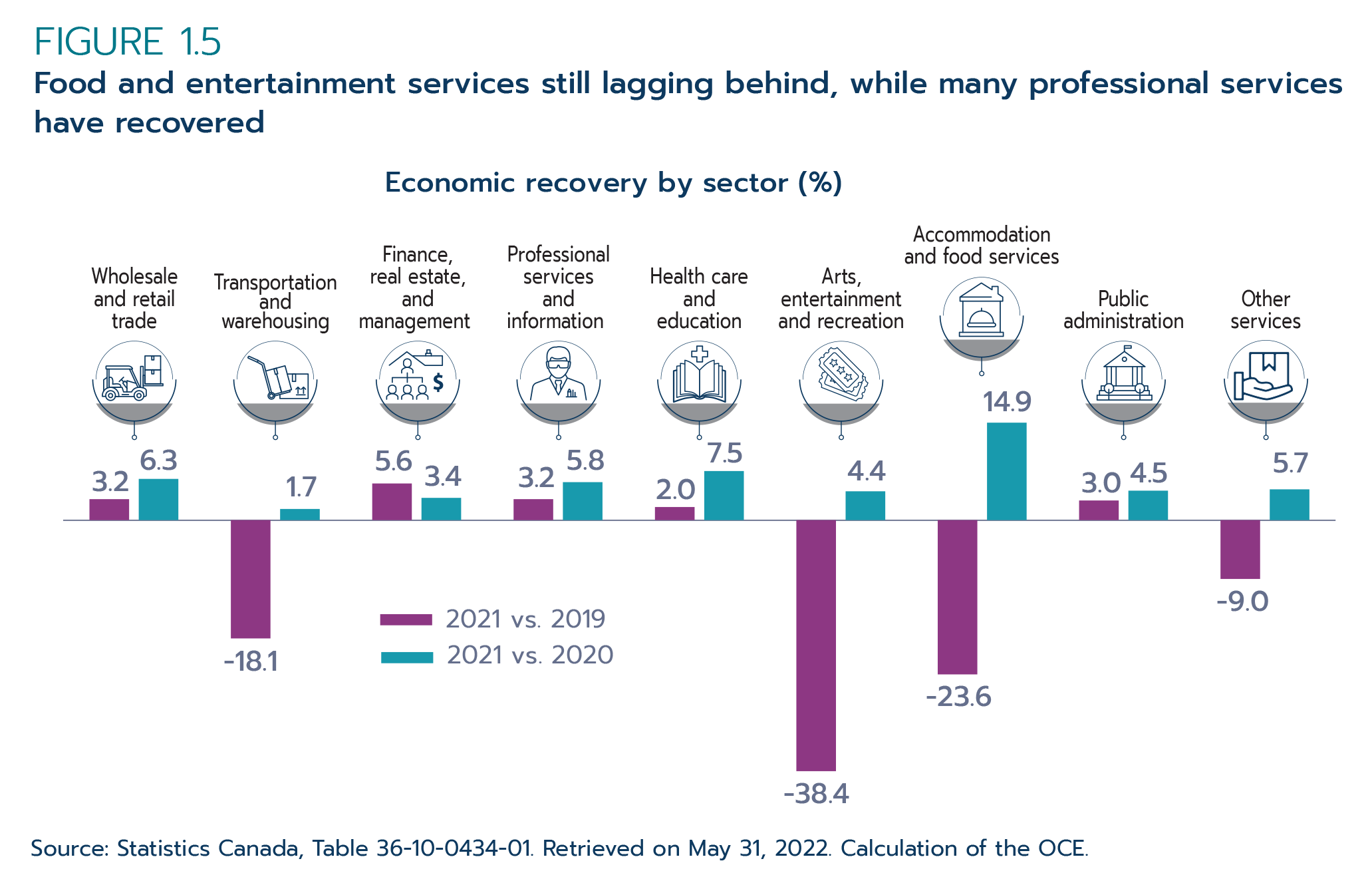

Services industries, especially those relying on face-to-face interactions, were some of the most impacted by the global COVID-19 pandemic and its related health restrictions. However, these industries began to recover in 2021, expanding 5.3%, outpacing the 3.9% growth for goods-producing industries (Figure 1.4). Every services industry except for management of companies and enterprises expanded. Top contributors to the growth were health care and social assistance, real estate and rental and leasing, and professional, scientific and technical services (Figure 1.5). Moreover, accommodation and food services, one of the hardest-hit industries in 2020, expanded by 14.9% in 2021.

Figure 1.4: While 2021 was a strong year, particularly for services, overall activity was lower than in 2019

Economic recovery by sector (%)

| 2021 vs. 2020 | 2021 vs. 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| All industries | 4.9% | -0.5% |

| Goods-producing industries | 3.9% | -2.0% |

| Services-producing industries | 5.3% | 0.1% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

Figure 1.5: Food and entertainment services still lagging behind, while many professional services have recovered

Economic recovery by sector (%)

| 2021 vs. 2019 | 2021 vs. 2020 | |

|---|---|---|

| Wholesale and retail trade | 3.2% | 6.3% |

| Transportation and warehousing | -18.1% | 1.7% |

| Finance, real estate, and management | 5.6% | 3.4% |

| Professional services and information | 3.2% | 5.8% |

| Health care and education | 2.0% | 7.5% |

| Arts, entertainment and recreation | -38.4% | 4.4% |

| Accommodation and food services | -23.6% | 14.9% |

| Public administration | 3.0% | 4.5% |

| Support and other services | -9.0% | 5.7% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

However, despite widespread growth, many services industries did not fully recover their losses from 2020. For example, in addition to management of companies and enterprises, leisure industries such as arts, entertainment and recreation, and accommodation and food services remained far below their pre-pandemic levels. For the year overall, the strong recoveries in some services (namely, real estate and finance) counteracted continued challenges in others, leading to total economic activity in services-producing industries being nearly equal to 2019 levels.

On the goods side, robust growth in mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction, construction, and manufacturing were partially offset by a slowdown in agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting and utilities industries (Figure 1.6). Furthermore, despite the substantial recovery in 2021, overall goods-producing industries posted a slower recovery than services-producing industries and remained 2.0% below their 2019 levels.

Figure 1.6: 2021 growth in many goods industries, but only construction has recovered to pre-pandemic levels

Economic recovery by sector (%)

| 2021 vs. 2020 | 2021 vs. 2019 | |

|---|---|---|

| Agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting | -6.5% | -3.4% |

| Mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction | 6.5% | -1.6% |

| Utilities | -1.4% | -3.8% |

| Construction | 5.8% | 3.6% |

| Manufacturing | 4.5% | -5.7% |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0434-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

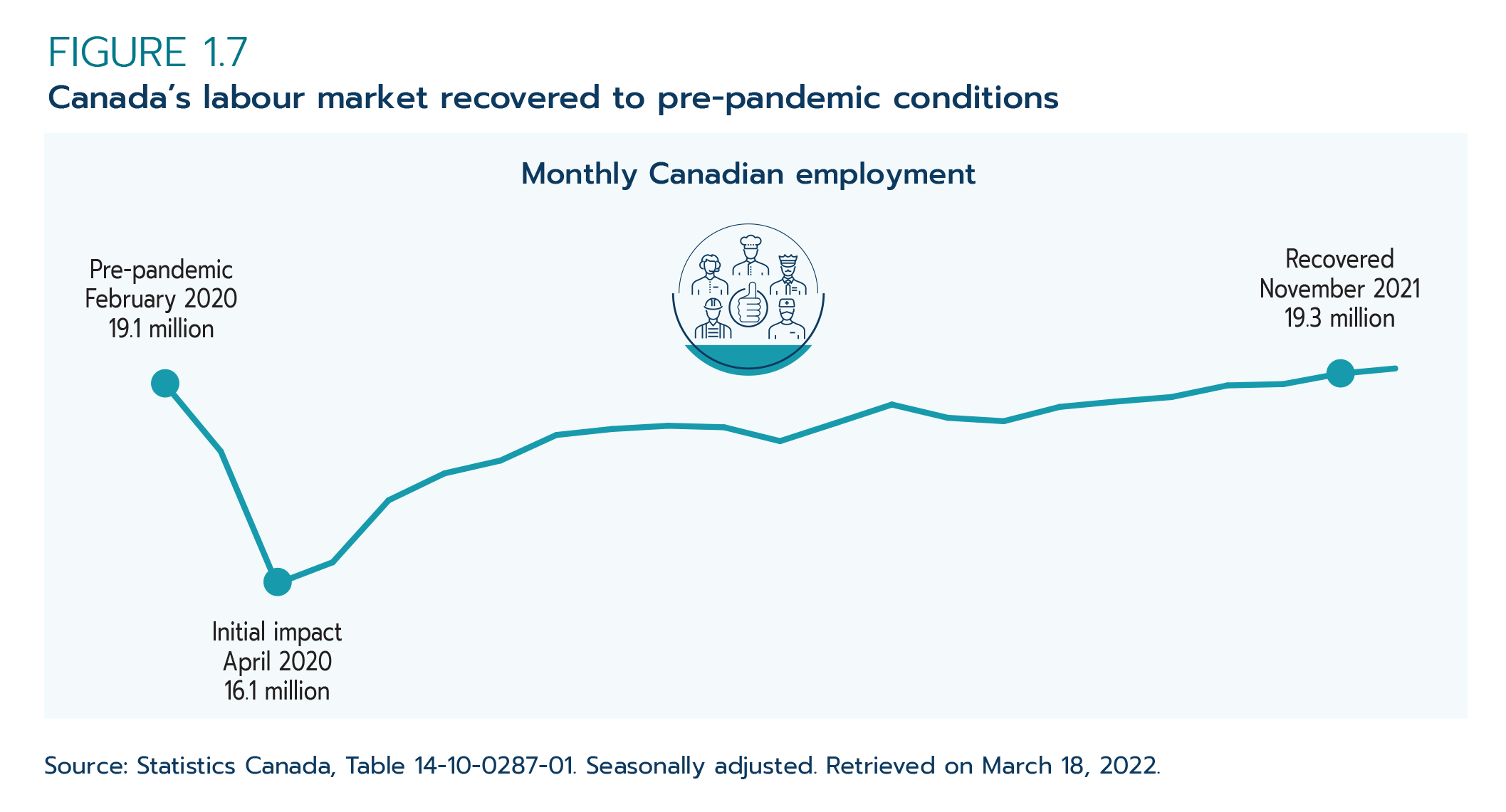

Due to strong employment growth, especially in the latter half of the year, Canada’s labour market largely recovered to pre-pandemic conditions by the end of 2021 (Figure 1.7). Monthly employment rose from a low of 16.1 million in April 2020 to 19.4 million in December 2021, surpassing the pre-pandemic level of 19.1 million recorded in February 2020. Moreover, other labour market indicators reached near pre-pandemic levels by December 2021: the unemployment rate fell back down to 6.0% (5.7% in February 2020), the participation rate rose to 65.4% (65.6% in February 2020), and the employment rate reached 61.5% (61.9% in February 2020).

Figure 1.7: Canada’s labour market recovered to pre-pandemic conditions

Monthly Canadian employment

| Month | Description | Number employed |

|---|---|---|

| February 2020 | Pre-pandemic | 19.1 million |

| April 2020 | Initial impact | 16.1 million |

| November 2021 | Recovered | 19.3 million |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01. Seasonally adjusted. Retrieved on March 18, 2022.

On the other hand, Canada experienced a surge in prices. The annual average consumer price index (CPI) was 3.4% in 2021, the highest annual inflation since 1991. Prices of goods had surged 4.7% and services by 2.3%. Most of the price increases took place in the second half of the year when monthly inflation accelerated to over 4.0% for most months. Due to global supply chain disruptions, prices for durable goods and food rose by 4.4% and 2.5%, respectively, for the full year. At the same time, elevated prices for oil and natural gas pushed up energy prices by 18.9%. When energy is excluded, annual inflation was only 2.4% in 2021, roughly the same pace as the 2.3% price growth in 2019.

Key data

There are a series of 3 graphics on Canada's trade:

Canada's exports to several markets had a record-breaking year

| Trade partner | 2021 export record value |

|---|---|

| Total exports | $766.3 billion |

| U.S. | $549.7 billion |

| Japan | $16.3 billion |

| South Korea | $7.4 billion |

| Taiwan | $3.0 billion |

| Spain | $2.6 billion |

| Indonesia | $2.4 billion |

Sources: Statistics Canada, International Monetary Fund, World Bank. Calculation of the OCE.

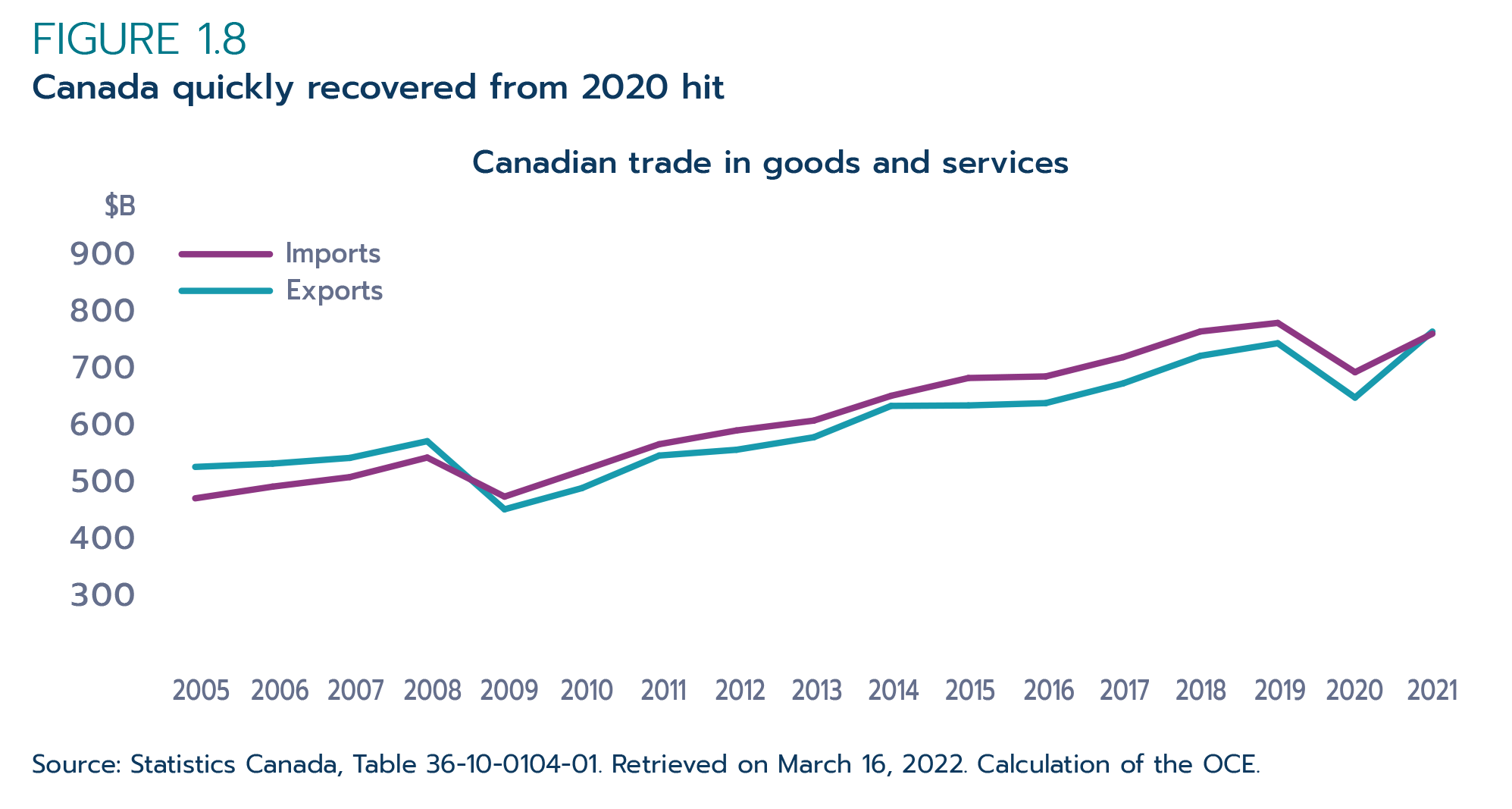

While Canada’s economy ended the year slightly below pre-pandemic levels, its international trade had a record-breaking year. Footnote 1 After a historical crash in 2020, Canada's 2-way trade in goods and services rose 14.1% in 2021 to reach a new record high of $1.53 trillion in value (up 0.2% from 2019). Exports were up 18.3% to $766 billion—a new record high—while imports advanced 10.2% to $764 billion, which remained 2.3% below 2019 levels (Figure 1.8).

Figure 1.8: Canada quickly recovered from 2020 hit

Canadian trade in goods and services ($ billions)

| Year | Import | Export |

|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 468 | 524 |

| 2006 | 489 | 530 |

| 2007 | 506 | 540 |

| 2008 | 541 | 570 |

| 2009 | 471 | 448 |

| 2010 | 517 | 486 |

| 2011 | 565 | 544 |

| 2012 | 589 | 555 |

| 2013 | 607 | 577 |

| 2014 | 651 | 633 |

| 2015 | 683 | 634 |

| 2016 | 686 | 638 |

| 2017 | 720 | 673 |

| 2018 | 766 | 723 |

| 2019 | 782 | 745 |

| 2020 | 693 | 648 |

| 2021 | 764 | 766 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0104-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

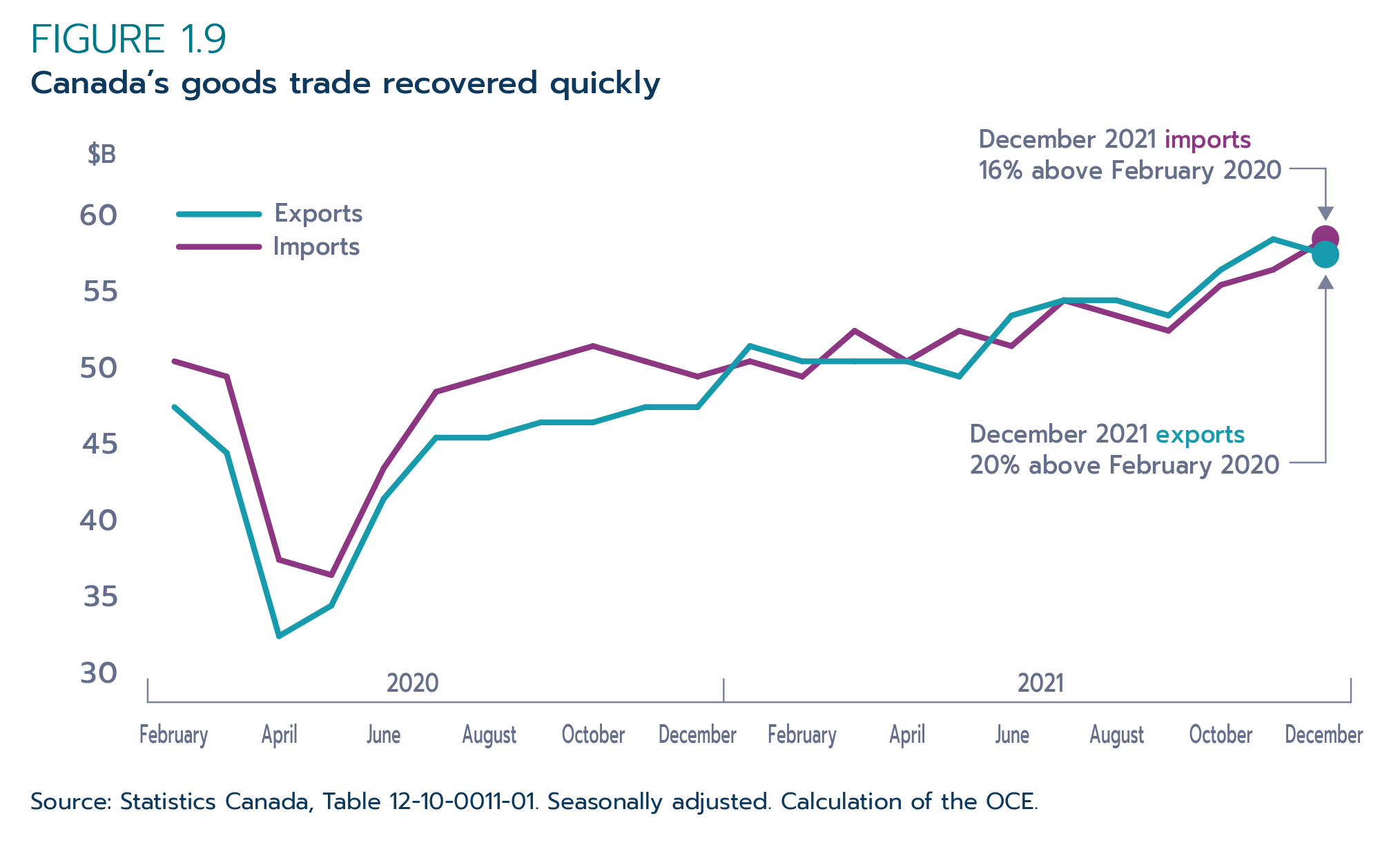

The historical growth in Canada's international trade was mainly due to a recovery in its trade of goods. Following a $125-billion decline in 2020, Canada's 2-way trade in goods increased by nearly $184 billion in 2021 to reach a new record high of $1.27 trillion in value (Figure 1.9). This represented 17.0% growth from 2020, putting total goods trade 4.8% above pre-pandemic levels in 2019.

Figure 1.9: Canada's goods trade recovered quickly

| Exports | Imports | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | February | 47 | 50 |

| March | 44 | 49 | |

| April | 32 | 37 | |

| May | 34 | 36 | |

| June | 41 | 43 | |

| July | 45 | 48 | |

| August | 45 | 49 | |

| September | 46 | 50 | |

| October | 46 | 51 | |

| November | 47 | 50 | |

| December | 47 | 49 | |

| 2021 | January | 51 | 50 |

| February | 50 | 49 | |

| March | 50 | 52 | |

| April | 50 | 50 | |

| May | 49 | 52 | |

| June | 53 | 51 | |

| July | 54 | 54 | |

| August | 54 | 53 | |

| September | 53 | 52 | |

| October | 56 | 55 | |

| November | 58 | 56 | |

| December | 57 | 58 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0011-01. Seasonally adjusted. Calculation of the OCE.

Goods exports registered an especially strong performance. Supported by resource products, Canadian goods exports were up by 21.9% in 2021 to $636 billion in value (a new record). However, these figures reflect changes to the value of exports, which include both volume and price effects (Box 1.1). The 2021 historical growth was largely due to elevated commodity prices. When the effects of prices are removed, the volume of Canada's goods exports only rose by 1.9% in 2021, still 5.3% below pre-pandemic levels in 2019. In contrast, the 12.4% rise in the value of Canada's goods imports (to $632 billion) was driven by both prices and volumes. In fact, the volume of imports increased 8.6% in 2021.

Box 1.1: Price or quantity effect? The impacts of the pandemic on Canadian exports

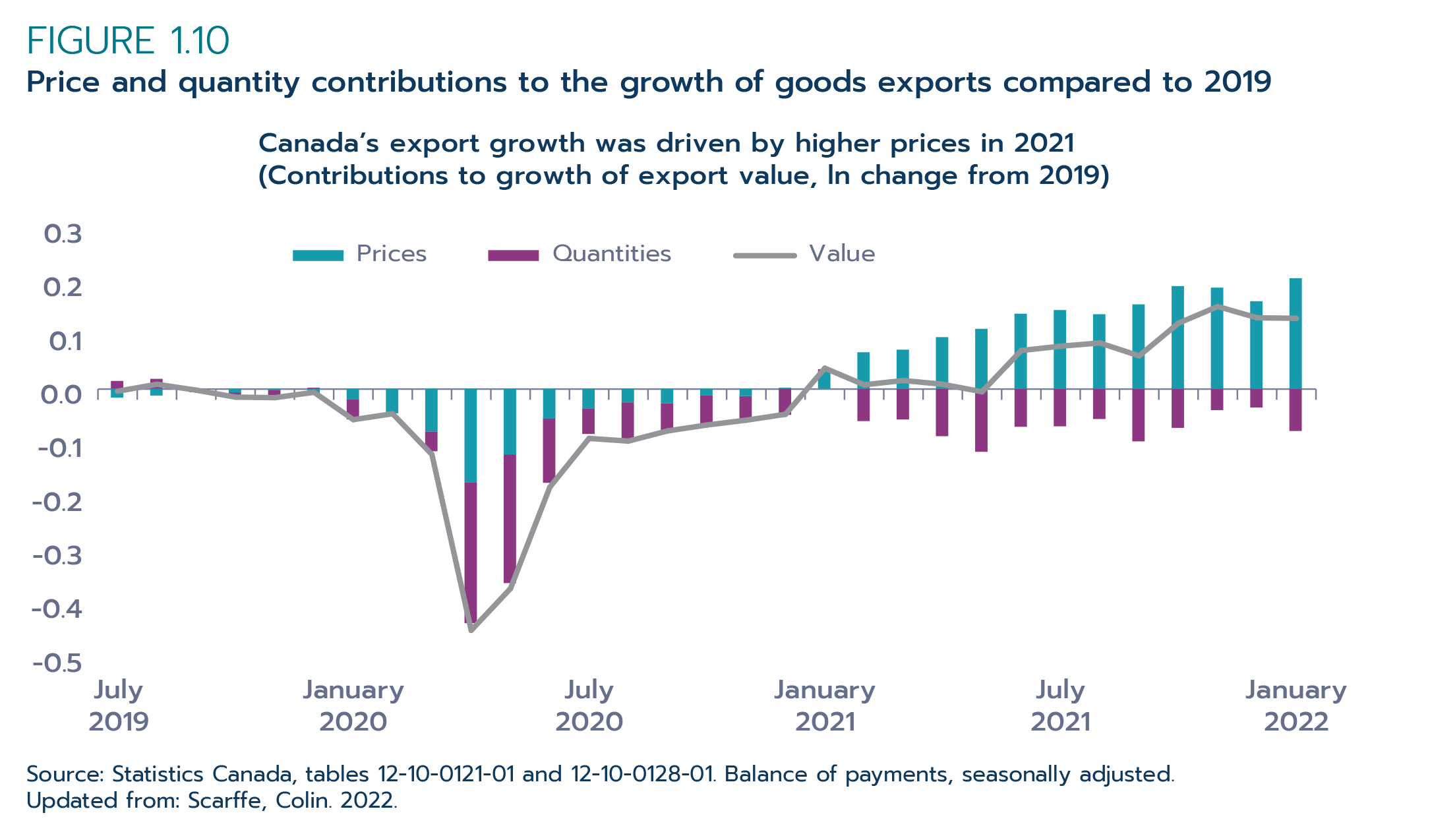

Between January and December 2021, the value of goods exports increased 9.9%—a strong year of growth by any standards. However, Figure 1.10 points to a curious event: this growth was actually the product of 2 offsetting trends. Over the course of 2021, export prices increased 14.7%, while the quantity (volume) of exported goods decreased 4.1%.

Figure 1.10: Price and quantity contributions to the growth of goods exports compared to 2019 Footnote 2

Canada's export growth was driven by higher prices in 2021

(Contributions to growth of export value, ln change from 2019)

| Month | Value | Prices | Quantities |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jan-19 | -0.034 | -0.029 | -0.006 |

| Feb-19 | -0.028 | 0.005 | -0.035 |

| Mar-19 | 0.013 | 0.025 | -0.010 |

| Apr-19 | 0.024 | 0.030 | -0.005 |

| May-19 | 0.053 | 0.021 | 0.032 |

| Jun-19 | 0.002 | -0.012 | 0.016 |

| Jul-19 | -0.004 | -0.017 | 0.015 |

| Aug-19 | 0.009 | -0.013 | 0.019 |

| Sep-19 | -0.002 | -0.005 | -0.002 |

| Oct-19 | -0.015 | -0.007 | -0.011 |

| Nov-19 | -0.016 | -0.003 | -0.016 |

| Dec-19 | -0.006 | -0.010 | 0.002 |

| Jan-20 | -0.057 | -0.020 | -0.039 |

| Feb-20 | -0.046 | -0.047 | 0.000 |

| Mar-20 | -0.122 | -0.082 | -0.038 |

| Apr-20 | -0.450 | -0.180 | -0.270 |

| May-20 | -0.372 | -0.126 | -0.247 |

| Jun-20 | -0.183 | -0.057 | -0.124 |

| Jul-20 | -0.092 | -0.038 | -0.049 |

| Aug-20 | -0.097 | -0.026 | -0.074 |

| Sep-20 | -0.078 | -0.028 | -0.056 |

| Oct-20 | -0.067 | -0.013 | -0.056 |

| Nov-20 | -0.058 | -0.014 | -0.046 |

| Dec-20 | -0.047 | 0.002 | -0.050 |

| Jan-21 | 0.039 | 0.032 | 0.006 |

| Feb-21 | 0.008 | 0.070 | -0.062 |

| Mar-21 | 0.016 | 0.075 | -0.059 |

| Apr-21 | 0.009 | 0.099 | -0.091 |

| May-21 | -0.005 | 0.115 | -0.121 |

| Jun-21 | 0.072 | 0.144 | -0.073 |

| Jul-21 | 0.080 | 0.151 | -0.072 |

| Aug-21 | 0.086 | 0.143 | -0.058 |

| Sep-21 | 0.062 | 0.162 | -0.101 |

| Oct-21 | 0.123 | 0.197 | -0.075 |

| Nov-21 | 0.154 | 0.194 | -0.041 |

| Dec-21 | 0.133 | 0.168 | -0.036 |

| Jan-22 | 0.132 | 0.212 | -0.081 |

Source: Statistics Canada, tables 12-10-0121-01 and 12-10-0128-01. Balance of payments, seasonally adjusted. Calculation of the OCE.

Updated from: Scarffe, Colin. 2022. “Price or quantity effect? The impacts of the pandemic on Canadian trade.” Global Affairs Canada. Ottawa.

The initial observation that strong export prices masked weak export quantities raised the question of whether a few products drove the trend or whether the trends were broad-based. Oil prices continued to significantly affect Canadian exports. The overall export price decline in 2020 was due entirely to the decrease in the price of oil. Likewise, the increase in the price of oil in 2021 accounted for 5.5 percentage points of the increase in export prices—yet this was only about a third of the total increase. Prices increased for 87 of the 101 exported products between January and December 2021 Footnote 3 . Thus while oil played a large role, the increase in export prices in 2021 was largely widespread and was not the result of an increase in price of a single product.

Similarly, regarding the quantity of goods exported, the implications of the observed trends differ depending on whether the cause can be attributed to a single product or widespread softness. Between January and December 2021, airplanes were the largest contributor to decreased export quantities. Low exports of airplanes can likely be attributed to lower demand due to the pandemic, as well as the generally intermittent nature of export sales of the products. However, 57 of the 101 products had lower quantities exported in December than they did in January. While this represents fewer products than the number of those experiencing price increases, a measure of concentration determined that the weakness was broad-based, indicating a more general slowdown.

In sum, the strength of Canada's 2021 export value was driven by prices, while quantities declined. The broad-based increase in export prices happened as economies around the world experienced the highest inflation in decades. Likewise, no single product was responsible for the lower export quantities. Both the increase in the prices and the decrease in quantity of goods exported were the symptoms of broader economic conditions.

The substantial growth in goods exports was primarily driven by higher exports of natural resources. Energy products, Canada's top export sector by far in 2021, led all sectors and expanded by 81.4% to a record high of nearly $135 billion in value (Table 1.1). This $61-billion increase in exports represented more than half of the total growth in Canada's goods exports. Exports of energy products were up mainly due to higher exports of crude oil. Besides energy products, forestry products, and metal and non-metallic mineral products each recorded growth of over $10 billion in value. Most other product sectors also recorded significant growth in 2021. Motor vehicles and parts was the only sector that contracted, falling by 4.3% or $3.3 billion, largely due to the prolonged global semiconductor shortage disrupting production activity.

| Industry | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 47.5 | 9.2 | 4.0 |

| Energy products | 134.8 | 81.4 | 60.5 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | 25.7 | 23.9 | 4.9 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | 76.6 | 15.3 | 10.2 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | 39.0 | 29.7 | 8.9 |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 54.8 | 31.7 | 13.2 |

| Industrial machinery, equipment and parts | 37.9 | 5.6 | 2.0 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment and parts | 27.0 | 4.9 | 1.3 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 72.0 | -4.3 | -3.3 |

| Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts | 24.2 | 7.1 | 1.6 |

| Consumer goods | 79.2 | 14.0 | 9.7 |

| Total | 636.3 | 21.9 | 114.1 |

| Imports | |||

| Farm, fishing and intermediate food products | 23.7 | 10.8 | 2.3 |

| Energy products | 32.1 | 39.2 | 9.0 |

| Metal ores and non-metallic minerals | 15.4 | -6.5 | -1.1 |

| Metal and non-metallic mineral products | 58.8 | 18.3 | 9.1 |

| Basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products | 51.8 | 25.7 | 10.6 |

| Forestry products and building and packaging materials | 30.2 | 16.2 | 4.2 |

| Industrial machinery, equipment and parts | 68.9 | 13.9 | 8.4 |

| Electronic and electrical equipment and parts | 74.2 | 9.1 | 6.2 |

| Motor vehicles and parts | 95.1 | 8.3 | 7.3 |

| Aircraft and other transportation equipment and parts | 19.9 | 2.4 | 0.5 |

| Consumer goods | 136.3 | 7.2 | 9.2 |

| Total | 631.7 | 12.4 | 69.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0122-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

On the import side, 10 out of 11 product sectors expanded in 2021. Consumer goods, the top import sector accounting for over one fifth of Canadian imports, increased by 7.2% to $136.3 billion in value. This growth was mainly because of increased imports of pharmaceutical and medicinal products, which included COVID-19 vaccines. Other import sectors with strong growth were basic and industrial chemical, plastic and rubber products, metal and non-metallic mineral products, and energy products. The only import sector that declined over the course of 2021 was metal ores and non-metallic minerals. Imports in this sector contracted by 6.5% largely because of lower imports of "other metal ores and concentrates".

Canada's goods exports experienced strong expansions to most of its top trading partners in 2021. Goods exports to the United States (U.S.) were up by $101 billion or 26.9%, representing almost 90% of the growth in export value for the full year (Table 1.2). This growth was largely driven by increased exports of energy products such as crude oil. As the rate of growth for exports to the U.S. outpaced that of other markets, the U.S. share of Canadian goods exports edged up 3 percentage points to 74.9%. At the same time, Canadian goods imports from the U.S. also registered a double-digit growth of 12.2%.

| Partner | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| United States | 476.7 | 26.9 | 101.0 |

| European Union | 31.0 | 9.1 | 2.6 |

| China | 28.6 | 10.2 | 2.7 |

| United Kingdom | 18.2 | -14.3 | -3.0 |

| Japan | 14.6 | 17.0 | 2.1 |

| Mexico | 8.9 | 32.7 | 2.2 |

| South Korea | 6.4 | 34.1 | 1.6 |

| Hong Kong | 3.6 | 87.2 | 1.7 |

| Switzerland | 3.2 | -34.8 | -1.7 |

| Norway | 3.2 | 22.6 | 0.6 |

| Other partners | 42.0 | 11.8 | 4.4 |

| Total | 636.3 | 21.9 | 114.1 |

| Imports | |||

| United States | 392.9 | 12.2 | 42.8 |

| European Union | 57.2 | 12.3 | 6.3 |

| China | 57.2 | 15.5 | 7.7 |

| Mexico | 19.6 | 15.4 | 2.6 |

| Japan | 11.2 | 11.7 | 1.2 |

| United Kingdom | 10.0 | 6.6 | 0.6 |

| South Korea | 8.6 | 14.8 | 1.1 |

| Switzerland | 7.3 | -29.2 | -3.0 |

| Brazil | 6.7 | 15.0 | 0.9 |

| Hong Kong | 4.9 | 18.0 | 0.7 |

| Other partners | 56.2 | 18.7 | 8.9 |

| Total | 631.7 | 12.4 | 69.7 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0023-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

China and Mexico were also important drivers of export growth. After an unprecedented fall in 2019 due to various trade disputes, Canada's goods exports to China improved for 2 consecutive years, despite the effects of the pandemic. In 2021, goods exports advanced by 10.2% (or $2.7 billion) to reach $28.6 billion in value, mainly supported by higher exports of metallurgical coal. Goods exports to Mexico posted the third-fastest rate of growth out of all of Canada's main export destinations, advancing by 32.7% in 2021 to $8.9 billion in value. This significant growth was mainly driven by farm, fishing and intermediate food products. Over the same period, goods imports from China advanced 15.5% with broad-based gains across many sectors, and goods imports from Mexico were up by 15.4%.

Canada's services trade began to recover in 2021 (Figure 1.11). However, the recovery was much slower when compared to goods trade. For the full year, Canadian services trade increased by 1.9% to $262 billion in value, with services exports growing by 3.3% and services imports advancing only 0.6% (Table 1.3). Overall services trade remained 17.4% below 2019 levels in 2021.

Figure 1.11: Services trade only began to recover in the second quarter of 2021

| Exports | Imports | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | February | 11.7 | 14.6 |

| March | 11.0 | 13.4 | |

| April | 10.1 | 9.9 | |

| May | 9.9 | 9.5 | |

| June | 9.9 | 9.9 | |

| July | 9.9 | 9.6 | |

| August | 10.1 | 9.6 | |

| September | 10.3 | 10.1 | |

| October | 10.4 | 10.1 | |

| November | 10.5 | 10.1 | |

| December | 10.4 | 10.0 | |

| 2021 | January | 10.4 | 10.4 |

| February | 10.3 | 10.0 | |

| March | 10.5 | 10.0 | |

| April | 10.4 | 10.3 | |

| May | 10.5 | 10.4 | |

| June | 10.6 | 10.7 | |

| July | 10.7 | 10.9 | |

| August | 10.9 | 11.1 | |

| September | 11.1 | 12.0 | |

| October | 11.4 | 11.8 | |

| November | 11.7 | 11.9 | |

| December | 11.9 | 12.3 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0144-01. Seasonally adjusted. Calculation of the OCE.

| Category | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| Travel | 16.5 | -9.1 | -1.7 |

| Transportation | 14.8 | 8.5 | 1.2 |

| Commercial services | 97.3 | 5.0 | 4.6 |

| Government services | 1.4 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

| Total | 130.0 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| Imports | |||

| Travel | 9.6 | -40.5 | -6.6 |

| Transportation | 26.7 | 14.9 | 3.5 |

| Commercial services | 94.2 | 4.1 | 3.7 |

| Government services | 1.5 | 7.9 | 0.1 |

| Total | 132.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0021-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

The negative economic impacts of COVID-19 public health restrictions were especially significant for services sectors like travel and transportation that involved face-to-face interactions. Transportation services partially recovered in 2021, with transportation services exports and imports rebounding by 8.5% and 14.9%, respectively. Yet transportation services trade was still 18.8% below 2019 levels. In contrast, despite signs of recovery in the second half of 2021, Canada's total travel services trade contracted for a second consecutive year, with exports falling 9.1% and imports decreasing by over 40% from the year prior.

Commercial services was the one services sector that was largely unaffected by the global pandemic. The resilience in this sector was in part due to businesses adapting to the difficult situation by accelerating their digital transformation (KPMG, 2021). Overall, after a small dip in early 2020, Canada's commercial services exports quickly recovered and surpassed their pre-pandemic levels. Similarly, commercial services imports held steady throughout the past 2 years. For the full year 2021, commercial services exports and imports rose by 5.0% and 4.1%, respectively, from 2020 levels.

After posting double-digit declines in 2020, Canada's services trade rebounded with many partners in 2021. Nevertheless, services trade with most of Canada's key trading partners remained below 2019 levels. Similar to goods exports, services exports to the U.S. led all countries and expanded by $4.9 billion in 2021 to reach $73.0 billion (Table 1.4). As Canada's overall services exports only expanded by $4.2 billion in total, increased exports to the U.S. represented the largest growth by far and resulted in the U.S. share of Canadian services exports rising from 54.2% in 2020 to 56.2% in 2021—the largest share since 2005. Services exports to the U.S. rose primarily due to a 6.5% increase in exports of commercial services. At the same time, services imports from the U.S. declined for a second consecutive year, falling by 2.5% in 2021 to $70.5 billion, as the $2.2-billion increase in commercial services imports was more than offset by a $3.8-billion decrease in imports of travel services.

| Partner | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exports | |||

| United States | 73.0 | 7.2 | 4.9 |

| European Union | 15.2 | 4.2 | 0.6 |

| United Kingdom | 6.0 | 3.3 | 0.2 |

| China | 5.2 | -9.1 | -0.5 |

| India | 4.4 | -12.5 | -0.6 |

| Switzerland | 2.0 | 2.4 | 0.0 |

| Mexico | 1.9 | 17.4 | 0.3 |

| Hong Kong | 1.8 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Japan | 1.6 | 3.1 | 0.0 |

| Australia | 1.0 | -1.7 | 0.0 |

| Other partners | 17.9 | -4.0 | -0.8 |

| Total | 130.0 | 3.3 | 4.2 |

| Imports | |||

| United States | 70.5 | -2.5 | -1.8 |

| European Union | 18.1 | 11.7 | 1.9 |

| United Kingdom | 8.1 | -5.2 | -0.4 |

| Hong Kong | 5.5 | 29.3 | 1.3 |

| Japan | 2.8 | 7.2 | 0.2 |

| China | 2.6 | 10.5 | 0.2 |

| Singapore | 2.6 | 27.8 | 0.6 |

| India | 2.4 | -1.3 | 0.0 |

| Switzerland | 1.7 | 1.3 | 0.0 |

| Mexico | 1.5 | -35.8 | -0.8 |

| Other partners | 16.3 | -2.1 | -0.4 |

| Total | 132.1 | 0.6 | 0.8 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 12-10-0157-01. Retrieved on May 31, 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

Outside of the U.S., Canada's services exports to other top trading partners only improved marginally in 2021. Supported by commercial services, Canadian services exports to the European Union (second-largest destination as a group) and the United Kingdom rose by 4.2% and 3.3%, respectively, in 2021. Services exports to Japan also rose 3.1% on the back of higher exports of travel and transportation services. Bucking the trend, services exports to China posted another decline, falling by 9.1% year-over-year. On the import side, services imports from the EU rebounded significantly, growing by 11.7%, as travel, transportation, and commercial services all increased. Services imports from the U.K. fell 5.2% due to lower imports of commercial services. In Asia, services imports from China and Japan recorded strong growth.

Key data

Stock of foreign direct investment in Canada, ultimate investor country basis, 2021

| Continent | Value 2021 | % share |

|---|---|---|

| North America | $567B | 52% |

| Europe | $290B | 27% |

| Asia & Oceania | $139B | 13% |

| South & Central America | $19B | 2% |

| Africa | $633M | 0.1% |

Note: Shares may not add to 100% due to rounding.

Source: Statistics Canada. Calculation of the OCE.

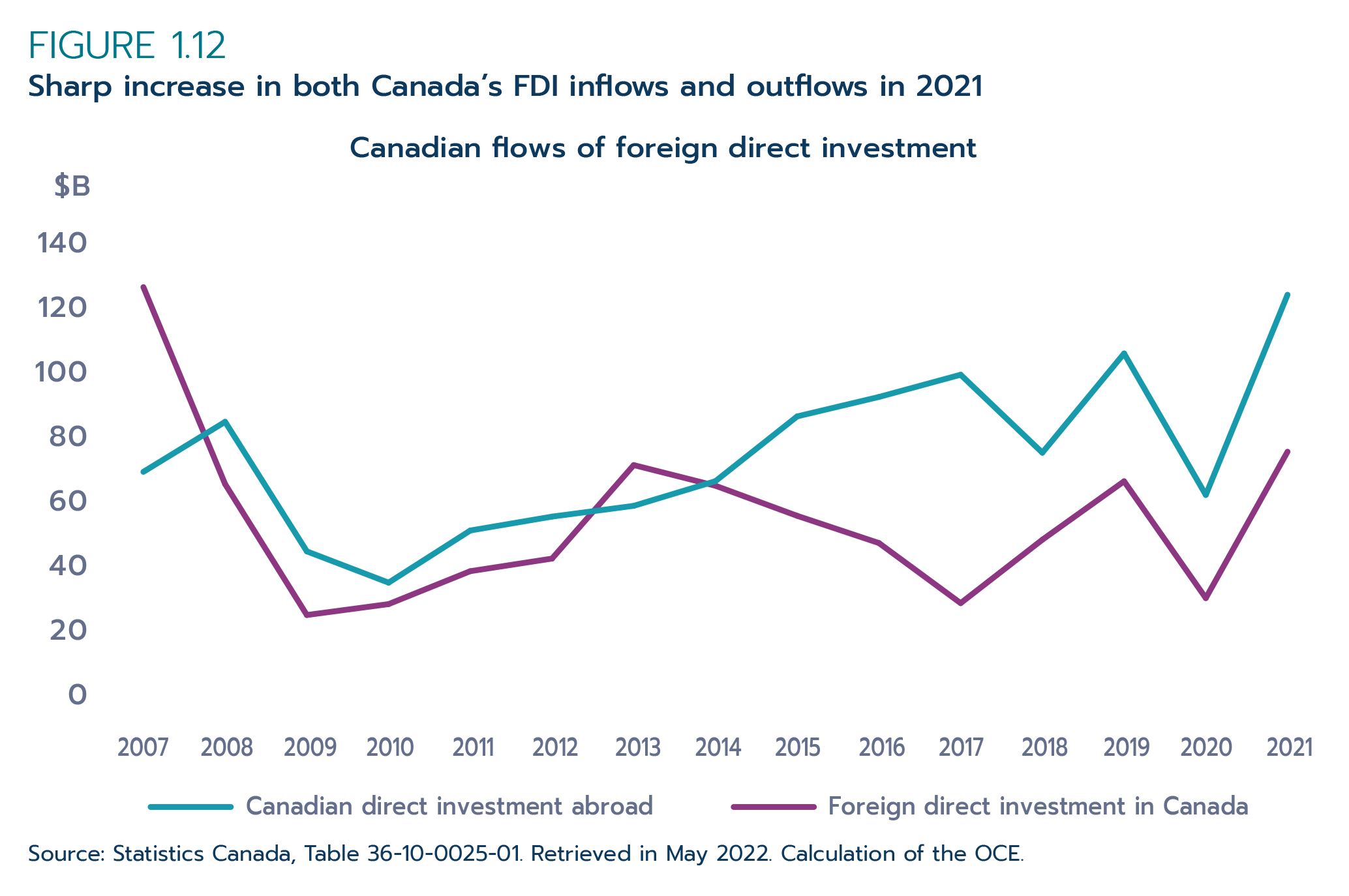

Mirroring the strong rebound in global foreign direct investment (FDI) flows, there was a solid recovery in both Canadian direct investment abroad (CDIA) and inward FDI in 2021 (Figure 1.12). Unlike the slow recovery following the 2007-08 global financial crisis and subsequent recession, CDIA and FDI flows rebounded quickly in 2021, with both surpassing their pre-pandemic levels. CDIA flows reached a record high of $123 billion in 2021, up 97% from 2020 and substantially higher than the $73-billion average of the 2010-2019 decade. Similarly, FDI inflows recorded the highest level since 2007 at $76 billion, representing a 143% increase from 2020 and 52% higher than the 2010-2019 average.

Figure 1.12: Sharp increase in both Canada’s FDI inflows and outflows in 2021

Canadian flows of foreign direct investment ($ millions)

| Canadian direct investment abroad | Foreign direct investment in Canada | |

|---|---|---|

| 2007 | 69,416 | 125,476 |

| 2008 | 84,592 | 65,679 |

| 2009 | 45,268 | 25,948 |

| 2010 | 35,770 | 29,257 |

| 2011 | 51,602 | 39,254 |

| 2012 | 55,819 | 43,076 |

| 2013 | 59,091 | 71,459 |

| 2014 | 66,584 | 65,186 |

| 2015 | 86,242 | 56,057 |

| 2016 | 92,140 | 47,796 |

| 2017 | 98,888 | 29,550 |

| 2018 | 75,221 | 48,803 |

| 2019 | 105,333 | 66,538 |

| 2020 | 62,400 | 31,082 |

| 2021 | 123,169 | 75,515 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0025-01. Retrieved in May 2022. Calculation of the OCE.

Mergers and acquisitions (M&As) contributed to most of the growth in CDIA, reaching the highest value since 2017 at $64 billion in 2021 and an annual growth of 242%. Reinvested earnings, or earnings from foreign affiliates invested back in the foreign affiliates rather than repatriated, rose at a much lower rate (52%). Conversely, Canada's growth in FDI inflows was largely due to a substantial increase in reinvested earnings. In 2021, reinvested earnings totaled $38 billion—over 10 times the level in 2020 and the highest value recorded since 2007, when it started being tracked. M&As also contributed to the growth in FDI inflows, increasing by 30% from 2020.

The trade and transportation sector accounted for almost half of the $123 billion in CDIA flows in 2021, surpassing the finance and insurance sector, which historically held the largest shares of outward investments by Canada. CDIA in the trade and transportation sector grew by more than a factor of 25, from $2.3 billion to $60 billion; it is likely that the Canadian Pacific Railway acquisition of Kansas City Southern (CP, 2021), completed in the last quarter of 2021, contributed to that increase. Management of companies as well as the energy and mining sectors also posted increases in CDIA flows in 2021, but not enough to match the historically high flows of 2019. Finance and insurance, manufacturing and "other industries" saw lower flows in 2021.

With respect to FDI inflows, the manufacturing, and energy and mining sectors accounted for almost half of the $76 billion inflows of 2021, followed by the trade and transportation sector. The management of companies sector received the least flows of FDI in 2021; the flows were 47% lower than in 2020. Among all sectors, including "other industries", management of companies was the only sector in which the 2021 flows remained below its 2010-2019 average.

The majority of the $44-billion increase in FDI flows recorded in 2021 was invested in the energy and mining sector, which went from a $8.8-billion disinvestment in 2020 to $17 billion in 2021. This injection of new investment into the sector was well above the 2014-2019 annual average but below the pre-pandemic level. Inflows in the manufacturing sector also greatly increased to reach $19 billion, 3 times that of the inflows in 2020. Finance and insurance, trade and transportation and "other industries" also posted growth, while investment flows in the management of companies and enterprises sector contracted and fell below 2019 levels.

| CDIA | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy and mining | 11.6 | 40.5 | 3.4 |

| Manufacturing | 2.1 | -63.0 | -3.6 |

| Trade and transportation | 59.6 | 2,542.0 | 57.3 |

| Finance and insurance | 29.7 | -2.0 | -0.6 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 13.8 | 144.5 | 8.2 |

| Other industries | 6.4 | -38.0 | -3.9 |

| Total | 123.2 | 97.4 | 60.8 |

| FDI | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

| Energy and mining | 16.6 | n/a | 25.4 |

| Manufacturing | 19.2 | 215.7 | 13.1 |

| Trade and transportation | 11.4 | 10.9 | 1.1 |

| Finance and insurance | 9.5 | 138.9 | 5.5 |

| Management of companies and enterprises | 4.6 | -46.9 | -4.0 |

| Other industries | 14.3 | 30.5 | 3.3 |

| Total | 75.5 | 143.0 | 44.4 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0026-01. Retrieved in May 2022. Calculation of the OCE. n/a: not applicable

Not surprisingly, the United States remains Canada's top investment partner, as the destination of two thirds ($78 billion) of CDIA and the source of almost half ($35 billion) of all FDI inflows in 2021 (Table 1.6). The U.S. was the main driver for Canada's 2021 investment recovery. About 66% of the $61-billion increase in CDIA flows between 2020 and 2021 were destined to the U.S.; it was the source of nearly half of the $44-billion growth in inflows of FDI.

Luxembourg ranked second among the main CDIA destinations of flows in 2021 (behind the "other countries" category), followed by France and Australia. The large growth in outflows destined for these 3 countries contrasted with limited flows to the United Kingdom and Switzerland, 2 important destinations for CDIA prior to the pandemic. Interestingly, in 2021, CDIA flows to the top 5 destination countries reached their highest levels since 2012 when data on flows were first recorded.

Looking at Canada's FDI sources, the Netherlands was the second main source in 2021, after the U.S., followed by the Cayman Islands and the United Kingdom (after the "other countries" category). With the exception of the 3 Asian partners (China, Japan and Hong Kong) Australia and Switzerland, FDI flows from all top 15 FDI source economies surpassed their pre-pandemic levels.

It should be noted that FDI flows refer to the last country where the investment comes from before arriving in Canada, including intermediary countries through which investments are channeled. While data on the ultimate source country of FDI flows are not available, Statistics Canada does produce data on FDI stock or FDI “positions” on both an ultimate investor country (UIC) and immediate investing country (IIC) basis. These data reveal that investments from some countries that are typically intermediaries, such as the Netherlands and Luxembourg, may have originated from other countries. Conversely, FDI flow data may understate FDI from countries that invest more via intermediaries, such as Japan and China. For more details about foreign investments on the UIC basis, see Chapter 2 of Canada’s State of Trade 2021.

| CDIA destinations | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 77.7 | 106.6 | 40.1 |

| Luxembourg | 7.1 | n/a | 7.2 |

| France | 4.2 | 266.3 | 3.1 |

| Australia | 3.2 | 80.4 | 1.4 |

| Brazil | 3.1 | 628.8 | 2.6 |

| Hong Kong | 2.7 | -42.6 | -2.0 |

| United Kingdom | 2.1 | 36.5 | 0.6 |

| Mexico | 1.7 | -57.2 | -2.3 |

| Japan | 1.6 | 500.8 | 1.3 |

| Germany | 1.3 | -32.1 | -0.6 |

| China | 1.0 | -10.9 | -0.1 |

| Switzerland | 0.8 | n/a | 0.9 |

| Cayman Islands | 0.3 | -19.3 | -0.1 |

| Netherlands | 0.2 | -77.3 | -0.6 |

| Barbados | -2.1 | n/a | -5.8 |

| Other countries | 18.4 | 449.6 | 15.0 |

| Total | 123.2 | 97.4 | 60.8 |

| FDI sources | Value ($B) | Change (%) | Change ($B) |

| United States | 35.1 | 132.4 | 20 |

| Netherlands | 9.6 | 67.0 | 3.9 |

| Cayman Islands | 6.4 | 816.3 | 5.7 |

| United Kingdom | 5.0 | 64.4 | 1.9 |

| Luxembourg | 4.1 | n/a | 8.5 |

| France | 3.2 | 442.3 | 2.6 |

| Switzerland | 2.4 | n/a | 6.7 |

| Brazil | 2.3 | 55.6 | 0.8 |

| Germany | 1.6 | 120.1 | 0.9 |

| Australia | 1.1 | n/a | 3.3 |

| Barbados | 0.3 | 29.3 | 0.1 |

| Mexico | 0.1 | -30.5 | -0.1 |

| China | -0.2 | n/a | -0.2 |

| Japan | -0.6 | n/a | -1.3 |

| Hong Kong | -1.2 | n/a | -0.2 |

| Other countries | 6.1 | -57.6 | -8.3 |

| Total | 75.5 | 143.0 | 44.4 |

Source: Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0473-01. Retrieved in May 2022. Calculation of the OCE. n/a: not applicable

In summary, 2021 was a recovery year for economies around the world including Canada. Businesses continue to experience elevated levels of risk and uncertainty during this recovery period and will need to use all the tools at their disposal to succeed. Free trade agreements (FTAs) are an important way for businesses to reach new markets and ensure that Canada benefits from commercial connections abroad. Canada currently has 15 FTAs that cover 61% of global GDP and give access to 51 foreign markets (Figure 1.13). Part 2 of this document will explore Canada’s experiences with FTAs and highlight Canada’s approach to assessing FTAs to ensure that the benefits of trade are felt by all Canadians.

Figure 1.13: Canada’s FTA network provides extensive access to global markets

Canada's 15 free trade agreements cover:

% Share of global GDP by Canada’s FTA partners in 2021

| FTA | % |

|---|---|

| CUSMA | 27 |

| CETA | 18 |

| CPTPP (excl. Mexico) | 9 |

| Canada’s other FTAs | 8 |

| Non-FTA partners | 38 |

Source: International Monetary Fund. Calculation of the OCE.

Note: The figures reflect ratification of the CPTPP agreement by all partners excluding Mexico.

For decades, free trade has been upheld as a central instrument for improving the living standards of individuals across nations. Broad acceptance of the merits of free trade and market-oriented policies over the past decades has contributed to a period of sustained growth and rising prosperity in many parts of the world.

The main merits of free trade are well known (GAC, 2012):

Free trade, as an instrument, was institutionalized under the auspices of the General Agreement on Trade and Tariffs (the GATT) in 1947. The GATT set the stage for multilateral trade liberalization, transforming the global trading system into the present one, which is governed by a set of rules and mechanisms. The GATT orchestrated 8 rounds of multilateral trade negotiations, for example, the Geneva Round in 1947, the Tokyo Round in 1973, the Uruguay Round in 1994, and most recently, the Doha Round, which is still ongoing. The Uruguay Round was concluded with the signing of the Marrakesh Agreement on April 15, 1994, which replaced the GATT with the newly formed World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995.

Since the inception of the GATT, the number of signatories increased from 23 in 1947 to 164 as of 2021. The average tariff levels for the major GATT participants were about 22% in 1947. After the Uruguay Round, however, the average tariff levels of GATT participants were under 5% (Brown and Irwin, 2017). That said, average tariff levels remained significantly high in many developing economies.

In addition to facilitating tariff reductions, the GATT also rationalized the global trading system by binding the negotiated tariff reductions permanently, establishing the generality of non-discrimination through most-favored nation (MFN) treatment Footnote 4 and national treatment clauses, ensuring greater transparency of trade policy measures, and providing a forum for the peaceful resolution of bilateral disputes. All of these elements contributed greatly to reducing trade barriers and improving policy certainty.

According to the historian Douglas Irwin, the prosperity of the world economy over the last half century owes a great deal to the growth of world trade that is in turn the result of the foresight of those involved in creating the GATT. Taking a longer-term view, the original GATT architecture helped put the world economy on a sound foundation, thereby improving the livelihoods of hundreds of millions of people around the world (Irwin, 2007).

However, as the WTO expands its membership, it becomes abundantly clear that reaching timely agreements among a large group of countries on a consensus basis at various stages of economic development, with different political and economic systems, values, and preferences is becoming an increasingly difficult task. At the same time, the negotiations of such agreements become even more complicated as the scope of trade liberalization goes beyond tariff reductions, additionally focusing on promoting cooperation among WTO members on a host of beyond-the-border issues. These include regulatory cooperation, intellectual property, government procurement as well as wider social policy issues related to environmental regulations and the protection of labor and human rights.

Due to the complexities associated with the multilateral route to trade liberalization, many countries—both developed and developing—choose the regional or bilateral route. As of 2021, the WTO has been notified of a cumulative 353 bilateral and regional trade agreements that have been put into force. The proliferation of bilateral and regional free trade agreements is reshaping the current landscape of the global trading system, leading people to weigh the merits and the disadvantages of such agreements.

Natural trading partners find it easier and quicker to reach a market access agreement because they are geographically close to one another and are already trading extensively with each other.

Working with like-minded countries that share similar political systems, values and culture makes it easier to find common ground for beyond-the-border issues in a bilateral or regional environment. These issues are part and parcel to domestic regulatory regimes that are deeply rooted in a country’s political and economic systems, as well as its culture and its religious and social values.

The desire to preserve a level playing field and recoup preferences Footnote 5 lost due to the formation of an FTA between other trading partners, along with other geo-political and strategic considerations, can motivate a country to launch FTA discussions with a potential new trading partner.

A growing trend in recent years has been the formation of the so-called mega-regional trade agreements, which involves the world’s 10 largest economies and many other countries located across different continents. These mega-regional trade agreements include the 11-member Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) and the 16-member Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). These agreements are significant because they account for a significant portion of world trade, covering substantial regulations governing international commerce in a wide range of areas, and therefore can drive up the costs of staying outside these mega-regional trading blocs significantly.

In spite of the contribution of increased global trade to global growth and prosperity, both for Canada and the world, some experts have questioned the benefits of the bilateral and regional approaches of FTAs. Critics argue that the proliferation of FTAs may create overlapping rules making it difficult for firms to navigate and to access the benefits of these agreements. Others like Bhagwati and Sriivasan (2002) argue that FTAs discriminate against non-members, who are unable to access the preferential treatment that these agreements create, making FTAs suboptimal from a broader economic welfare perspective.

In a number of jurisdictions, there is ongoing public debate over the extent to which FTAs may contribute to a relative decline in employment and wages of workers in some sectors. Nonetheless, policy-makers and many economists remain convinced by the evidence that FTAs remain an effective policy tool to lower trade barriers, improve market access, promote greater trade between nations and increase economic welfare. This paper explores and assesses many of these issues in closer detail, along with a review of literature, to inform our findings.

Canada’s embrace of free trade dates back to the 1850s and 1860s when Canada was part of British North America.

In 1854, Britain entered into the Elgin-Marcy Treaty (also known as the Reciprocity Treaty) with the United States of America. As part of British North America, Canada was included in this treaty. However, the U.S. government abrogated the agreement in 1866.

In 1911, the United States agreed to enter into a free trade arrangement with Canada, but this initiative was abandoned when the Liberal government that had initiated the trade discussions lost the election (Policy Options, 2007).

In 1987, Canada and the United States successfully concluded the Canada-United States Free Trade Agreement (CUSFTA). Canada was motivated to enter into the CUSFTA to secure access to the largest market in the world in the face of rising protectionism in the United States. The CUSFTA provided Canada with an opportunity to address its domestic agenda, namely to increase the competitiveness of Canadian industries and to boost its national productivity, which had consistently lagged that of the United States for decades.

The CUSFTA was later expanded to include Mexico, leading to the formation of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA).

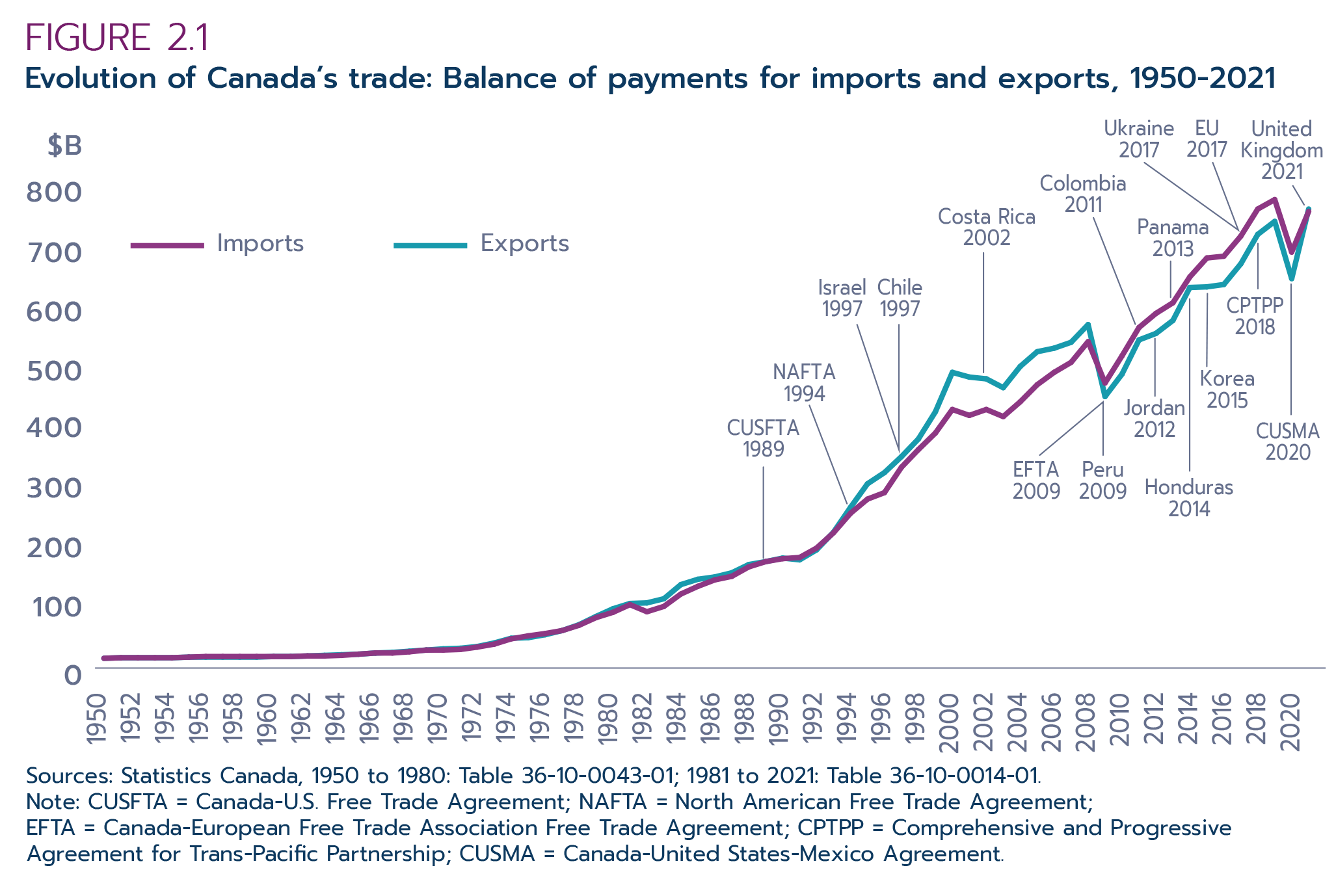

Since the successful implementation of the CUSFTA, Canada has embarked on numerous FTA initiatives and set in motion a series of bilateral and regional trade negotiations that concluded with 15 bilateral and regional trade agreements covering 51 countries across Europe, Latin America and Asia (Figure 2.1). The Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) allowed Canada to expand trade with its second-largest trading partner, the European Union, which was also one of the world’s largest economies at the time of inception in 2017.

Figure 2.1: Evolution of Canada’s trade: Balance of payments for imports and exports, 1950-2021

| Year | Imports | Exports |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 4 | 4 |

| 1951 | 5 | 5 |

| 1952 | 5 | 5 |

| 1953 | 5 | 5 |

| 1954 | 5 | 5 |

| 1955 | 6 | 6 |

| 1956 | 7 | 6 |

| 1957 | 7 | 6 |

| 1958 | 7 | 6 |

| 1959 | 7 | 6 |

| 1960 | 7 | 7 |

| 1961 | 7 | 7 |

| 1962 | 8 | 8 |

| 1963 | 8 | 9 |

| 1964 | 9 | 10 |

| 1965 | 11 | 11 |

| 1966 | 13 | 13 |

| 1967 | 13 | 14 |

| 1968 | 15 | 16 |

| 1969 | 18 | 18 |

| 1970 | 18 | 20 |

| 1971 | 19 | 21 |

| 1972 | 23 | 24 |

| 1973 | 28 | 30 |

| 1974 | 37 | 38 |

| 1975 | 42 | 39 |

| 1976 | 46 | 44 |

| 1977 | 51 | 51 |

| 1978 | 60 | 61 |

| 1979 | 73 | 75 |

| 1980 | 82 | 88 |

| 1981 | 95 | 97 |

| 1982 | 83 | 98 |

| 1983 | 92 | 105 |

| 1984 | 113 | 129 |

| 1985 | 126 | 138 |

| 1986 | 137 | 142 |

| 1987 | 143 | 149 |

| 1988 | 159 | 163 |

| 1989 | 168 | 168 |

| 1990 | 173 | 174 |

| 1991 | 175 | 171 |

| 1992 | 191 | 188 |

| 1993 | 217 | 218 |

| 1994 | 250 | 260 |

| 1995 | 274 | 300 |

| 1996 | 285 | 319 |

| 1997 | 328 | 346 |

| 1998 | 358 | 376 |

| 1999 | 386 | 422 |

| 2000 | 426 | 489 |

| 2001 | 416 | 481 |

| 2002 | 426 | 478 |

| 2003 | 414 | 463 |

| 2004 | 439 | 499 |

| 2005 | 468 | 524 |

| 2006 | 489 | 530 |

| 2007 | 506 | 540 |

| 2008 | 541 | 570 |

| 2009 | 471 | 448 |

| 2010 | 517 | 486 |

| 2011 | 565 | 544 |

| 2012 | 589 | 555 |

| 2013 | 607 | 577 |

| 2014 | 651 | 633 |

| 2015 | 683 | 634 |

| 2016 | 686 | 638 |

| 2017 | 720 | 673 |

| 2018 | 766 | 723 |

| 2019 | 782 | 745 |

| 2020 | 693 | 648 |

| 2021 | 762 | 766 |

Lines on the chart identify the years in which Canada had an FTA come into force:

| FTA | Year in force |

|---|---|

| CUSFTA | 1989 |

| NAFTA | 1994 |

| Israel | 1997 |

| Chile | 1997 |

| Costa Rica | 2002 |

| EFTA | 2009 |

| Peru | 2009 |

| Colombia | 2011 |

| Jordan | 2012 |

| Panama | 2013 |

| Honduras | 2014 |

| Korea | 2015 |

| Ukraine | 2017 |

| EU | 2017 |

| CPTPP | 2018 |

| CUSMA | 2020 |

| United Kingdom | 2021 |

Sources: Statistics Canada, 1950 to 1980: Table 36-10-0043-01; 1981 to 2021: Table 36-10-0014-01.

Note: CUSFTA = Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement; NAFTA = North American Free Trade Agreement; EFTA = Canada-European Free Trade Association Free Trade Agreement; CPTPP = Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership; CUSMA = Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement.

The trade data accumulated over 30 years since Canada first concluded the CUSFTA with the United States is enough to assess the costs and benefits of free trade and globalization in general—that is, whether FTAs have delivered on their promises to achieve expected outcomes—and to ask what lessons can be learned from the past FTAs.

Part 2 of this report will highlight various aspects of FTAs. Section 2.1 focuses on the trade creation effect of FTAs, using the recently completed ex post impact assessments of the Canada-Chile FTA and the Canada-Colombia FTA as examples. Section 2.2 explains the welfare implications of Canada’s FTAs. Section 2.3 considers the labour market implications of these agreements, featuring the results of recent research on the Canada-U.S. FTA. Section 2.4 goes beyond tariffs to explore beyond the border aspects of FTAs such as environment and labour. Finally, Section 2.5 gives an overview of the interplay between diplomacy and FTAs.

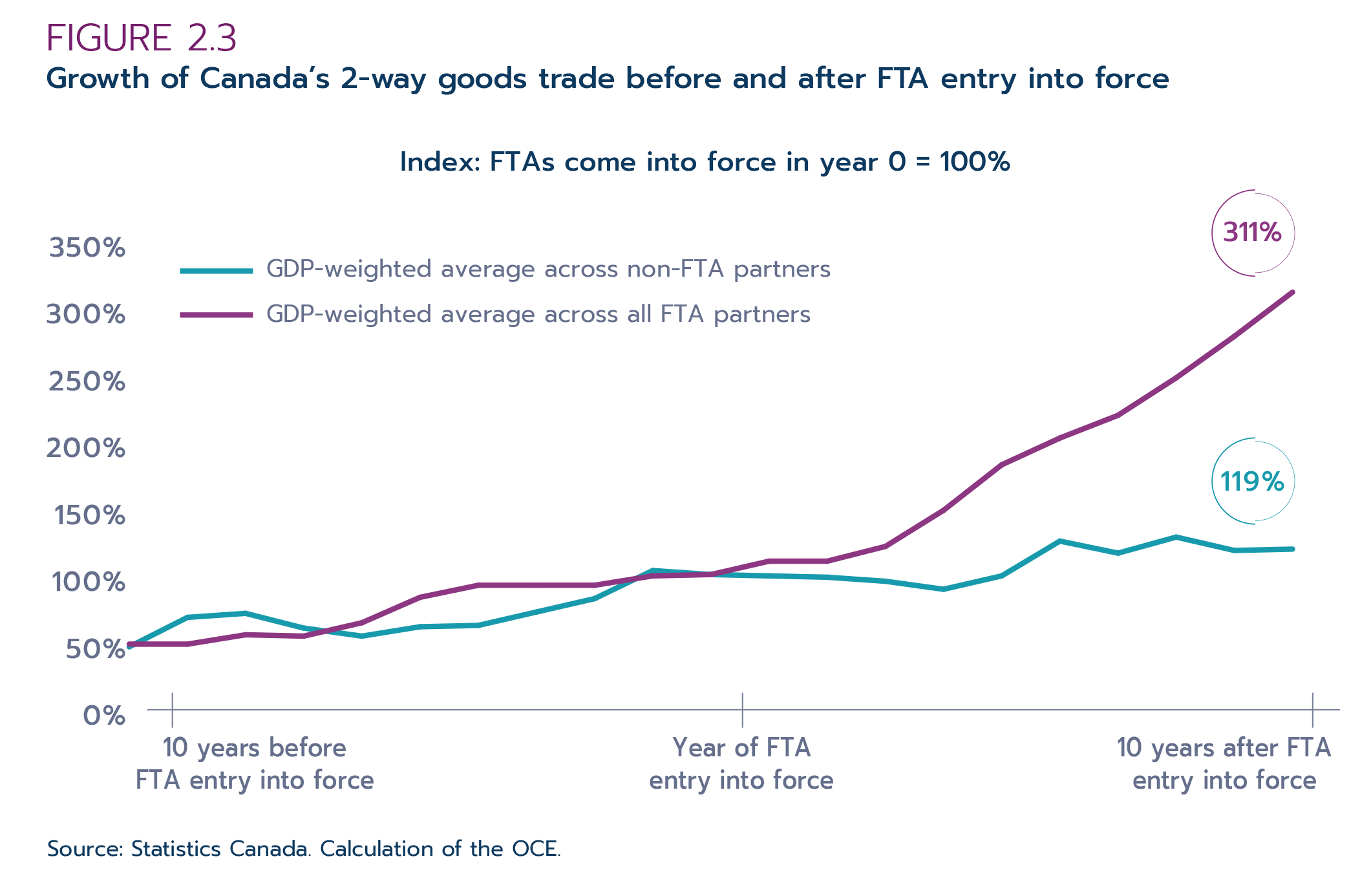

If a free trade agreement (FTA) is working as intended, one would expect more trade to be created between the FTA partners. This is because an FTA provides reciprocal preferences between countries that are party to the agreement, but does not extend them to non-FTA parties that continue to trade under most-favored nation (MFN) status. Therefore, one of the larger questions surrounding FTAs is whether the improved market access they are meant to create actually results in increased trade between the FTA partner countries. Assessing this should be the first step before embarking on any other analysis of the effect of trade agreements.

To investigate the question of trade creation by FTAs, many different comparisons and quantitative analyses need to be carried out. This analysis will start by presenting general trends of bilateral trade between Canada and its FTA partner countries since the implementation of FTAs, followed by decomposing the bilateral trade by comparing the trade performance from different perspectives to detect the signs of trade creation under FTAs. While these comparisons help to illustrate trade gains under various FTAs, they cannot be considered as indicators of a causal effect of an FTA. Thus, a more sophisticated econometric analysis is needed to isolate the trade creation effect of FTAs from other factors that also influence trade flows, such as exchange rate fluctuations, change in commodity prices, and general market conditions in the partner countries.

Specifically, the investigation of the trade creation effect of FTAs will be carried out in the following steps: